Oil price: where next?

Posted by Euan Mearns on July 24, 2009 - 10:10am in The Oil Drum: Europe

One thing that was anticipated in the run up to peak oil was that the oil price would become volatile. Volatility leads to uncertainty creating difficulties for national governments, economic planning agencies and oil companies to plan ahead. One consequence of this has been the postponement of many large new oil field developments creating concern that future supplies may be insufficient to meet demand leading to a new oil price crunch in the years ahead.

So what is the right price for oil? To what extent can market mechanisms be relied upon to strike the right price? Is it possible to make sense of the volatile price signal shown in Figure 1?

Figure 1 Global total liquids from the IEA, data compilation kindly provided by Rembrandt Koppelaar. Oil price data from Economagic. All data are month averages.

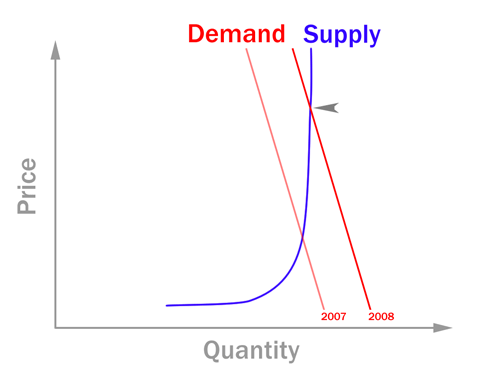

Last year Phil Hart provided us with a model to explain the relationship between oil supply, demand and price (Figure 2). Put simply, demand is inelastic in that it does not vary much owing to price variations alone - we still drive our cars even though it gets more expensive to do so. Supply used to be elastic (the flat part of the supply curve), higher prices easily translating to higher supply. In the real world this meant OPEC opening the taps on spare capacity. But then in 2004 the supply rules changed. OPEC spare capacity effectively fell to zero (Figure 1) and new supply became inelastic (steep part of the curve), i.e. higher prices did not lead to a ready flow of new oil since new capacity had to be built, at great expense, using expensive energy. The result was escalating prices and the spike of 2008.

Figure 2 Phil Hart's oil price, supply, demand model.

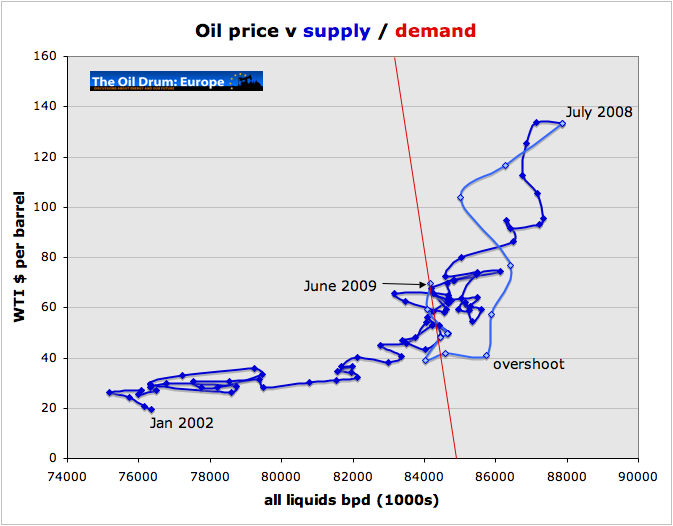

Somewhat surprisingly (for me at least) cross plotting the data from Figure 1, provides a picture that is still consistent with Phil's simple model (Figure 3). To understand Figure 3, the blue line is a time line, charting the evolution of supply / demand and price since January 2002 through to June 2009. Once production hit 84 mmbpd (million barrels per day) the plateau was effectively reached and expanding capacity in the face of 4.5% annual decline became an arduous task. Prices rose to keep supply and demand in balance until the peak in July 2008 when the economic crisis took hold leading to a collapse in demand.

Figure 3 Monthly oil production data (from the IEA provided by Rembrandt Koppelaar) and monthly average oil price data from economagic fit Phil Hart's simple model. The return path since July 2008 is shown in light blue. Marks at one month intervals.

Following the time line down from the July 2008 peak, the oil price overshot its mark by about $40, but since then it seems to have been correcting back towards the trend set during the ascent. First, the price stabilised at $40, tracking left as demand continued to fall. And then demand stabilised at about 84 mmbpd and the price rose from 40 to over $70 per barrel. The June 2009 position is within the trend set during the price ascent of 2006 and 2007, and on this basis I'd conclude that we have seen a correction back towards market equilibrium rather than a "dead cat bounce" in oil price.

The integrity of this trend from January 2002 to June 2009 is surprising since there have been large movements in OPEC spare capacity, which is adjusted to maintain supply in balance with demand. I suspect the fundamental reason to explain this is that global production capacity has remained fairly constant throughout this period. If there was to be a dramatic increase or decrease in productive capacity then this trend would break down

So that leaves the $60,000 question. Where next for the oil price? I believe that plateau supply of 84 to 88 mmbpd are secure for a couple of years as this summary of mega-projects compiled by Tony suggests (Figure 4). Therefore, the near term price will be controlled by demand. If the trend of Figure 3 holds good, then we could expect prices to rise towards $80 / bbl if demand rises by 2 mmbpd (likely spiking higher than that) or conversely falling to below $40 / bbl if demand drops a further 2 mmbpd, which is the scenario considered by Rune last month.

Figure 4 TOD megaprojects production capacity forecast compiled by Tony Erikson.

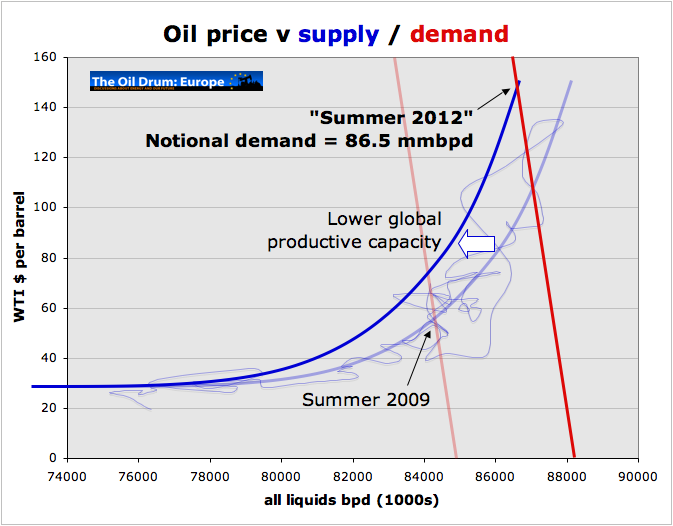

Longer term, productive capacity will begin to play a role and one can envisage how a fall in capacity of around 1 mmbpd may shift the supply demand relationship to the left. Combined with marginal growth in demand will result in a new price spike as shown in Figure 5. It is impossible to be precise on timing, but my best guess would be 2012±2 years, subject to the global banking system surviving the current crisis and the global economy resuming growth in 2010.

Figure 5 Scenario showing how a drop in productive capacity of around 1 mmbpd may move the supply curve to the left, combined with an increase in demand from 84 to 86.5 mmbpd, may result in a new oil price spike in excess of that seen in July 2008. Squiggly line is real data from Figure 3.

In a recent post I argued that there was a limit to the oil price that the global economy can bear. Any new price spike, as the name suggests, will be short lived as high price will kill demand and we will likely see a repeat performance of the 2008 crisis. At some point global leaders need to awaken to the prospect of that supply curve marching to the left, always.

I think peak oilers generally underestimate the ability of the demand curve to rotate counter clockwise to become a more shallow slope.

As someone with no formal education in economics I hesitate to criticise, but it does seem to me that the demand curve for 2009 should be shallower than that for 2008, reflecting the fact that in the hard times we find ourselves in fuel is more of a luxury (greater elasticity of demand) than in the recent past. The two curves would intersect the x axis at the same point. You would still get an intersection of supply and demand at a lower price.

Don't worry, even economists have no formal education in economics. I took a class in college where the teacher wrote a long equation on the chalkboard, stepped back, and then quickly erased it, saying that is the last bit of math that we would see.

The difficulty with supply/demand curves for people to grasp is that they are one of the best examples of implicit mathematical formulations that you will run across. My theory is that since math teachers do not understand implicit equations themselves, no one else really gets these either.

The math behind economics has a huge learning curve. Just look at the squiggly line that Euan has in that figure, as it has multiple multi-valued points. There is no gradual build-up in working economics out, its like you learn to add currency in explicit terms, and then bang!, you have the implicit supply-demand curves.

So the fact that peak-oilers fail to see how these supply-demand curves work, I would contend that no one really can see how this works. It is not how we have been trained in mathematics.

Nicely stated. One can never abuse economists too much. They are all fair game.

excellent , thats going into my sig - if you don't mind!

cheers

Forbin

Don't be surprised if you get replies online from people like me--an economist who's run a site about peak oil and climate chaos for over five years and gives public presentations on those topics--calling you very rude names for painting with such a broad, willfully ignorant brush.

After all, anyone who does something that counterproductive is fair game.

thanks for your concern, lou.

I have no troubles with this one, though....

"Oil - anyone who thinks you can continue to use finite resources indefinitely is either a mad man or an economist."

I'll refrain from the other one then, might be pushing my luck!

Cheers

Forbin

Did anyone else see the cover of the recent Economist magazine?

http://www.economist.com/printedition/displayCover.cfm?url=/images/20090...

Then there's the cover of the most recent Adbusters mag.

https://www.adbusters.org/magazine/85

Are those supposed to be economist beating someone up or a gang beating up an economist?

Any good ideas on solving the explicit equations as shown in Phil Hart's Figure 3? Doing it graphically is one thing, but I imagine there is some other way to do it. Shouldn't be too bad with an implicit equation solver and an interpolation scheme..

For those wanting to know more about how flawed neo-classical economic theory is, you might try following Steve Keen:

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs

I agree that the demand curves do not need to be straight or have same gradient over time, but this is a simple model. One also needs to recall that this is a global model, and not one exclusively for the US or OECD.

True, hardship may reduce the slope, whilst lower price is fighting to steepen it.

Never underestimate the power if explicit and implicit subsidies. Assume oil went to 200 and Obama introduced a 2000 per person economic stimulus check etc.

Or other less obvious subsidies. And of course China has cash to underwrite subsidies.

Given economic contraction is economic suicide for fiat currencies one has to imagine that they will print until it does not work.

Gotta move to Oregon so later.

A couple of points. All currencies that are fiat given that they are worth what people believe they are worth. If the belief disappears then the value of the currency drops according to that belief. So the term "fiat currency" is redundant.

For the government to issue $2,000 stimulus would mean the economy was in far, far worse a state than it is now. For that to happen unemployment would likely be in the 25% range. There is no way we can gauge what such a desperate measure would have on the price of oil... or other commodities for that matter.

What is the maximum price of oil before a total economic collapse? I believe that is the question even though the word "before" is only implied. And to what extent does is the supply and price of oil responsible for the state of the economy. That is, how high can the price of oil go without causing the economy to collapse.

Everything in the economy is tied together, interwoven in a very complex economy. To what extent did the housing and then the banking collapse cause the economic crisis? And to what extent was the high price of oil responsible for the housing and banking collapse?

That is where most of us made our mistake last year. Most of us simply assumed that demand was largely inelastic and the price would eventually hit $200, then $300 and higher as demand stayed static while the supply declined. It never dawned on us that a the economy was about to suffer a near meltdown. And we were all shocked at the dramatic effect this had on the price of oil.

There is no doubt that the price of oil has had, and will continue to have, a strong effect on the health of the economy. And that effect will determine just how high the price of oil can go.

Ron P.

"To what extent did the housing and then the banking collapse cause the economic crisis?"

90%

"to what extent was the high price of oil responsible for the housing and banking collapse?"

10%

On the contrary, 0% and 100%. The housing and banking collapse were (very) arguably caused by rising oil prices.

The collapse was inevitable.

147 Oil was the trigger event.

The housing collapse was caused by a huge departure of housing prices from historical ratios of housing affordability. Housing was a classic bubble. Oil prices certainly helped it pop and oil prices helped it pop more dramatically in the exurbs. But the prices were unrealistic and would have popped eventually anyhow.

This is easy to see by googling on ratios for housing costs to income and other similar ratios. You can find housing affordability indexes and ratios that stretch back over decades. Starting in the mid 90s those indexes and ratios started on an unsustainable bubble path.

Do let this site's oil obsession blind you to other causes of historical events. I say that as someone who writes on my own blogs about the approach of Peak Oil and about how our lives will be disrupted by Peak Oil.

The housing bubble was starkly obvious as it was being inflated.

The metrics you refer to are both simple and intuitive.

Makes you wonder if Greenspan et al are idiots or criminals.

porge, Yes, the housing bubble was extremely easy to see in a graph over time. Glaringly obvious. The departure of the US from a historical ratio of buying a house about 3 times yearly inncome wasn't caused by Peak Oil.

Lenders raised allowable debt-to-income ratios above the historic 28% (28% of income going to housing debt service, home insurance, and other ownership expenses) and this caused the housing bubble. Historic percentages of home ownership departed from trend in 1995. It took all the way until 2006 before the bubble started to burst and it is still bursting.

Peak Oil helped pop the bubble. But it was going to pop anyway. All bubbles come to an end.

Not so coincidentally, guess what other "charts" departed from historic trends in 1995?

Put any of the major Stock averages on a log chart and you will see the line up-tilt starting in 1995.

The NASDAQ of course being the most ridiculous.

It was explained away as the "peace dividend" because of the reduction in military spending after the cold war ended.

All this nonsense is a result of America tuning into a nation of paper pushers and gamblers for lack of real work. Between technological advancment making many occupations obsolete and off-shoring anything that could be people just turned to grabbing whatever they could grab.

Speaking in "isms"

America has gone from capitalism => financialism=> swindlism=> I guess next is collapsism??

The 700B stimulus package (which isn't including the bank or auto bailouts) works out to $2300 per US citizen.

EIT!

Darwinian,

you wrote "All currencies that are fiat...." - this implies that there are currencies that are not fiat, i.e. have constant value. I think this is not true,

a l l c u r r e n c i e s a r e f i a t

While the gold bugs are howling, think about it: you cannot eat gold, and it does not keep you warm. In a real crisis, people will sell their gold and try to buy wheat and fuel - poof goes the value of gold. Anybody who thinks a real (Western Roman Empire, 3rd or 5th century AD style) collapse is coming, should not buy any currency, but only real value (canned food, seeds, guns, ammo, fire wood, diesel fuel etc.)

or, reading further down your post, was this exactly what you meant?

Biologist, that was a typo on my part. I meant "All currencies are fiat". Sorry for the typo.

Ron P.

currency is too hard to define.

Fiat means "by decree".

So if we used say something of utility like salt as currency than it would be barter right?

If it is a marker you are correct about the confidence game but if the "currency" actually has another real use to me then it has value separate from the function of money.

Energy/resourced based economics solves everything.

"While the gold bugs are howling, think about it: you cannot eat gold, and it does not keep you warm. In a real crisis, people will sell their gold and try to buy wheat and fuel - poof goes the value of gold"

Biologist, Why would anyone want to eat money? Because that's what gold is, money. Or do you think we will go back to bartering? It's easy to forget just how useful an invention money was, e.g. for those occasions when the person with the cow didn't want to trade it for your beans. And gold has, over centuries, proven itself the perfect money. Not for any abstract reasons but because it has all the properties that make it perfect for the job - divisibility, durability, scarcity, portability, hard-to-forgeability etc. Can't say the same for paper currency or its electronic equivalent with which trust is implicit and required. When that trust breaks down what form of money will people turn to? Interesting that Zimbabweans have been panning for small amounts of gold to buy bread with.

Don't confuse arguments about what should best be used as money with the underlying usefullnes of money.

TW

"food's so high today it's durn near cheaper to eat money," quipped Dick Gregory Monday as he spoke to a packed in audience at Evans Auditorium. ..."

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1065&dat=19740221&id=IbUMAAAAIBAJ&...

Ron wrote:

"There is no doubt that the price of oil has had, and will continue to have, a strong effect on the health of the economy. And that effect will determine just how high the price of oil can go."

Another possibility is that oil goes to the highest bidder AND there are still players that can afford oil while an increasingly large number of people cannot.

Demand is likely to be very fragmented across economic social status and across local, state, and nation-state boundaries. It is more complex to think of it this way and the 'supply & demand' curves become infinite and fractal in nature.

To clarify my previous comment, the aggregate demand/supply intersection for global oil may be deceptive about what is really happening--changing 'access' to oil in a probable scenario where the price continues to rise, particularly in the long run--regardless of the economy, say, of the United States, a debt-ridden nation state whose primary user of oil is the military-industrial complex which will continue to use its share despite the poverty of its citizens.

Thank you for this insightful data plotting Euan.

Euan,

"Put simply, demand is inelastic in that it does not vary much owing to price variations alone"

This is true short term, but we have evidence that over a longer time period( several years) structural changes are made in response to high prices. For example in US after 1980, a big reduction of oil used for electricity generation and heating oil replaced by NG and electricity.

On the 5 year horizon, we should see a shift to higher fuel economy vehicles and PHEV's, perhaps some conversion of light trucks to CNG, further replacement of heating oil, a reduction in jet fuel and further replacement of gasoline by ethanol(10E to 15E). These changes could account for a 20% reduction in oil consumption in US.

I agree that time scales are important. There's a number of things going on - poorer folks simply doing without, others opting for more fuel efficient solutions and substitution - EVs, electric rail etc. All this to some extent balanced by expansion of car ownership etc in the developing world.

Euan,

If the demand curve is really that steep over a short time period, that would indicate that people don't give up driving if they have a car, after all fuel is only a small part of the budget. What I find surprising is that people don't seem to even moderate driving very much based on fuel prices, this may be because once you have a vehicle most of the costs are still there(payments, insurance) even if its parked, and alternatives such as taxi, public transport can be expensive alternatives compared to just fuel costs.

Will the curve actually become steeper in time as people who can use mass transit switch and vehicles become more efficient, the remaining lower consumption will be really non-responsive to prices, perhaps requiring rationing to stop ridiculously high prices.

I think your right about people's driving, especially in rich countries. Most people only make major changes in their behavior when they encounter a crisis. Not all people are this way, but most are.

I'm not sure you're right about the demand curve in the future. I'm skeptical that it can get meaningfully steeper in the US, anyway. OTOH, if volatility becomes the norm, people may get more adaptable, making for more elastic demand and a shallower curve. I wonder, for example, if Iraq might currently have a much shallower curve than many other places, given all the adaptability people have no doubt had to learn there in the last few years. I'm speculating, but it seems plausible to me. Cultural and political factors will play a role. It seems like there are various plausible scenarios.

As Euan said above, the demand curves shown in the graphs look like linear functions (not curves at all actually), but that's a simplification, too.

I think you are correct -- right now many people think of their energy use as inelastic because they "have to" drive 45 minutes each way to work, or "have to" drive to the supermarket down the street, or "have to" run their air conditioning during the summer and heating during the winter.

Just imagine how much less elastic it will become after people simply have to quit those jobs with a 45 minute drive and either telecommute, train, etc, because fuel is either prohibitively expensive or unavailable.

OTOH, once energy consumption collapses far enough, renewables will actually be able to produce a fairly large fraction of our actual energy "needs" (or at least so I hope).

I suspect we will simply redefine "inelastic" over time, until our energy use is forcibly no larger than that we can generate quasi-sustainably (I say quasi because I question humanity's ability to actually exercise the discipline to not consume all resources it can find regardless of the long-term cost).

My use is inelastic (because I have plenty of income to pay for gas) as long as I remain employed. I think this is key -- demand destruction will necessarily be driven by either fuel rationing or job/wage loss.

I think jobs will be the eternal focus -- people were go wherever the jobs are, and will do whatever they can be paid to do.

Unfortunately, as jobs go away and are slowly recreated, the new jobs will be lower-paying, so wages WILL go down. How can it be otherwise?

Euan, the best information presentation is that which describes complexity with a simple a gaze and is inspirational.

That Figure 3 is brilliant. That chart speaks volumes about the supply curve and demand destruction. Figure 4 is also excellent. Based on these two alone, this should be one of the posts of the year.

Is figure 4 NET (net of depletion) additional productive capacity?

In figure 4, how much of the NET additional productive capacuty is NGLs versus others (conventional etc.)?

Well said. I concur regarding Figure 3 in particular.

Thank you Mr Cagney. I'll let Tony answer your question. The megaprojects list includes C+C+NGL and syncrude (I believe) but I don't know the split. I think its time we had a megaprojects up-date.

Hi Buster,

Figure 4 represents gross capacity additions of crude, oil sands, condensate, NGL, GTL and CTL. Ethanol is excluded. To get forecast production additions, a discount factor of about 15% should be applied.

NGL capacity additions can be calculated by adding up NGL additions from each year of the megaprojects data. As an example, 2008 and 2009 NGL capacity additions are shown below.

From 2008, 310 kbd NGL from Saudi Arabia and 180 kbd from Iran.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_megaprojects_(2008)

From 2009, Iran 80 kbd, Qatar about 300 kbd, and Saudi Arabia 280 kbd and UAE 135 kbd.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oil_megaprojects_(2009)

Please note that these NGL capacity additions aren't having the expected impact of increasing world NGL production. To the contrary, world NGL production is decreasing. 2007 was 7,956 kbd, 2008 was 7,938 kbd and 2009 YTD average April was 7,878 kbd.

http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/ipsr/t13.xls

Nice work again Yoon. (you clearly has an Apple product to make those graphics..)

I think your Figure 3 is excellent, but may lead to false conclusion that high price in July 2008 created the downward light blue line that follows. There were many other impacts afoot that aren't encapsulated by price/production.

To wit, the US FED monetary base, (the blue line), which had been increasing at 45 degree angle for some 90+ years, went straight up after July 2008 in the below Federal Reserve Graph:

I.e. it was not oil price that caused the demand drop, (though it likely contributed), but a massive global margin call and subsequent (and ongoing) credit crisis. My guess is you could create similar monthly supply/price graphs like Figure 3 for most commodities and they would all peak in July 2008 and have a similar looking retracements - this would be interesting endeavor. (except gold and maybe a few others - pork bellies, etc.) But I suspect think mathematical formulations and correlations at this point can only get us so far - the degree that fiat instruments have pulled our system away from physical reality won't be graphically 'known' until years in the future.

Here is another chart showing how this is much more than oil supply problem:

If current estimates hold, Q3 2009 will be first quarter since data has been kept when SP500 earnings will be negative (they are down 98% from Q3 2007 peak currently)

In any case, the most important point of your post is the last sentence:

Rhetorical question: if we could PROVE that supply has hit a wall, and that demand would dictate price of oil from here on out, would it change anything? I.e. would indications of permanent leftward shift of supply curve suddenly make policymakers change to a better course? I suspect not but, as always, hope that I'm wrong.

Whilst agreeing that there were / are a multitude of reasons for the July 2008 correction, I do believe that energy prices / scarcity was a key issue. If oil supply could have risen easily to 95 mmbpd, $30 / bbl, I suspect that economic leveraging would have continued onto new tiers. I suspect this may be why the economists "didn't see it coming". Algorithms and policies that worked for decades suddenly broke down as folks were spending too much on energy and not enough on everything else.

precisely, the real keys are "why didn't we see it coming" and "why do we never learn from things we don't see coming". If one were looking for the next great insight it would be to look for the great contradictions that everyone ignores.

It's ridiculous that the 6 year commodities price spiral, only ending in the collapse of finance and demand, clearly conflicts with all the laws on economics on which the macro-economic models are based and no one noticed. Wouldn't one think such a thing would raise a vigorous discussion? Nope, no one's really interested, seeming to do with it pushing people beyond their comfort zones.

Nate--I can suggest and suspect that the sudden switch to downward oil prices-- the downward light blue line--was partly something to do with speculation (in the quazi-opposite direction to the Matt Simmons' hypothesis). But those two graphs you've put there, most interesting as they are, I fail to see how they would not be direct consequences of oil becoming too expensive, to a point of crossing some balance-sheet thresholds. Surely that would obviously make S&P earnings nosedive (along with airlines), and also cause the massive global margin call.

By the way, there's no such thing as a 45% gradient unless the x and y axes are in the same units of measurement. (And on my screen it looks more like 18% anyway. (Maybe trig isn't your hottest talent?!)

Figure 3 caught my eye as well. I'd like to think there's a definitive strange attractor buried in there.

I'm thinking that another illustrative graph would be instead of plotting oil production vs. price, plot oil production vs. the relative value of oil to other necessary goods. The WTI price divided by the price of a bushel of wheat and/or the price of copper. Maybe further expand by relating to the agricultural and commodities indexes.

If I can get motivated, maybe I'll try to throw something together.

I'm surprised that no one picked up on your comment, 710, because it's apparent that the USD is being manipulated and stressed at the same time, so our oil/$ plots are a convolution of two independent variables.

I'd like to see your WTI versus ag commodities alternative plots; graphing oil price versus other industrial commodities (like Cu) might be more meaningful to models of the developed world.

You could model it on a second order differential equation reacting to unit step unit of input as in control theory.

Price(t)=A*diff(x*x,t)+B*diff(x,t)+C*x(t)+ K1;

The step input K1 would be the sudden entry of the various BRIC/developing economies demand into the world oil trade(something that won't change IMO). The amount of overshoot would depend on the value of B/A.

If B/A=0, there will be an endless cycle of price spikes and crashes(not the case here).

The gradual onset of peak oil(-2% per year) effect of Peak Oil would have a much less dramatic effect on increase in prices than the entry of BRICs as it would resemble a unit ramp input.

Price(t)=A*diff(x*x,t)+B*diff(x,t)+C*x(t)+ K1 + K2*diff(x,t);

Unfortunately, it reduces B to B-K2 it suggests greater volatility in a tighter range(which is attractive to speculators--not investors).

Of course, all this presupposes some kind of consistent pricing model acting like a second order diffeq which is rather dubious.

Do you have any examples worked out?

Is diff(x,t) a delta/difference formulation?

If you like but I can't find freeweb posting anymore for results. Why doesn't TOD offer it?

diff(x,t) is Maple-speak for dx/dt.

The only reason I used a second order diffeq was that that function gives overshoot(so I manifest curve-fitting disease).

But I thought to give it a go after all the IPCC models the entire planet climate as a first order diffeq

LOL ;-)

One question is whether the forcing is a step function(actual upsurge in BRIC demand due to globalization) or dirac's impulse function(crazy doomer speculators).

What is interesting is what is the Peak oil forcing function?

I chose unit ramp for slow steady depletion cause slow stead increase in price. If so it also reduces the overall system dampening(very bad).

Based on this model, rather than see immediate skyrocketing oil prices(unit step) you would see greater price swings clobbering a manic world economy as prices inexorably rise(unit ramp).

All just fun mathematical speculation.

Try something, I'm interested but I am not a mind reader.

Okay-dokey WHT,

The base price is $50/barrel. The year to year per dollar increase based on 2.2% depletion is $1.1 per barrel(2.2% x $50), the effect of BRICs entering oil market is $50 per barrel step function--a one time disruption. Time is biannually, so 50 units is 25 years. It's an exercise in curve-fitting but at least it differentiates big events like globalization from incremental ones like a 2% depletion rate.

Too bad it isn't as wild as the usual models at TOD.

> ode := |-- y(x)| + 0.2 |--- y(x)| + y(x) = 50 Heaviside(x) + 1.1 x + 50

> ics := y(0) = 50, y(1) = 100

> serias := dsolve({ics, ode}, y(x))

>plot(rhs(serias), x = 0 .. 100, y = 0 .. 300)

Here is Figure 3 extended back to 1970, with Tony Eriksen's May price prediction plotted in green (zero-scaled, price inflation-adjusted, production as crude+lease rather than total liquids):

Tony's projection ought to plot a locus of supply / demand line intersections - i.e. a locus of the intersections of your red and blue curves as they vary over time. But it actually looks pretty much like a straight line at a slope much like one of your red demand lines.

Guess that means the demand curve is what governs price once supply becomes scarce ... which is what you said, of course. So we get a phase shift from predominantly supply controlled price to predominantly demand controlled price.

G.

Gergyl - great chart! Any chance you can plot and post the time series (like my Figure 1) for the 3 data series you have (including Tony's forecast). The circular group is quite intriguing - it would be interesting to try and understand the process of its formation.

Tony's negative gradient curves represent rising price with falling production - which I always had on my diagnostics list for peak oil. I think you'll find the data are plotting the locus of intersections of supply and demand - falling supply playing a key role. Whilst Tony has a bit of volatility in his model, I think the real world will be much more volatile.

Euan,

Thanks for the great post. You and Gergyl have identified the wall clearly.

Dave

Great chart which I will add to my collection to wake up people with.

However, you overlook that there is a time-factor hiding in there. Supply is vvvery inflexible in the short term. Arguably it's now becoming very inflexible in the anything-at-all term too. But you can see on that same chart how it has been flexed upwards by 10mbd since the opec crisis (and less short-term inflexible back then, due to spare cap "on tap").

The circle would reflect an oscillating condition with a 90 degree phase shift between supply and demand -- in other words 1/4 of the period - wouldn't it? I suspect that is a function of the real-world delay in funding new projects, overshooting production, then swinging back the other way, shutting down rigs, etc.

I had seen other comments postulating the rapid rise in oil price was due to a shift from marginal cost of supply (which is slowly going up now) to the marginal cost of demand (which was high when everybody felt rich, but is likely lower now). If this view is accurate then we're going to bang back and forth between these until they converge, and then there might be less volatility but still some nasty economic realities as the wall marches left.

Hi Gregyl,

This is an excellent graph. I wonder if you could color the upwards spikes of early and late 1970 separately so that we could see the run up and fall back pattern. I bet it looks very similar to the 2008 price spike and collapse, despite the lack of a banking system collapse, but it would be very interesting to see for real.

As prices are rising by monetary inflation, and whole US economy was changing structure, I wonder how the Y axis could be rescaled to get a better comparison? Perhaps size of energy sector as % of GDP? Such as Euan wrote for his piece on the maximum price of oil?

I posted this a couple days ago in another comment but it's worth adding here.

I remember this from last year. Is this now updated? Can you clarify what is going on with the two data clouds in the 50 to 60 mmbpd range? What is the time range for the plot?

This is updated to April of 2009 (goes all the way back to January 1973). The Upper Cloud in the 50-60 MMBPD range is the period from 1979 to 1985 where the oil production peaked and then fell and oil prices were "high" (and they would be if chained to any particular date). Finally, prices fell rather steeply in late 1985 and then returned back to the Lower Cloud.

You can see this on the left side of this graphic which includes the same data as the curve previously posted.

More likely the supply did not change simply the reported numbers change. In fact I suggest this is a pretty big smoking gun that indicates that nothing has really changed as far as real oil goes.

Is it not possible that as long as there was ANY spare capacity that pricing was driven by the marginal costs of production, and only in 2009 did the spare capacity drop to effectively zero, entering a demand-control phase?

Fear not! All will be well.

This return email from the CEO of a government institution a few hours ago...

"I share some of your concerns about the planet's capacity to absorb population growth and what strains that growth will place on our ability to meet the needs of the international community. However, I think we can take comfort from the ingenuity of the human species and its ability to meet the technological and material challenges that lie ahead. My advice to the younger generation is 'be concerned and be watchful, but also be optimistic about humankind's ability to overcome the challenges ahead'."

Regards, Matt B

PS. The institute's motto reads: "There are no limits"

Sounds like they probably have more "Economists" than physicists and "Real" mathematicians on staff.

It is precisely when I hear BS like that, that my optimism for humankind's ability to overcome the challenges ahead, tends to wane considerably.

On the other hand, there doesn't seem to be a limit for humanity's capacity for self delusion.

ah got it!

"There are no limits - for humanity's capacity for self delusion."

thats the bit missing.........

Forbin

I'm just about to walk past an office block whose door proclaims "Only enter with a can-do attitude". To which I think: A can-make-pigs-fly attitude? Can-turn-water-into-oil attitude?

PS--the business in question has gone bust.

I wonder if there would be a difference between this CEO's viewpoint and the CTO's? The thing that really strikes me is how passive his `advice' is: 'be concerned and be watchful, but also be optimistic'. If he was suggesting that he and everyone getting his advice were to start developing this future (rather than the nebulous "ingentuity of the human species"/"humankind" who are somehow always supposed to be dramatically more ingenious and inventive than the speaker is) I might start to take him seriously.

Great work Euan! Peak oil is defined here in historic terms:

"...in 2004 the supply rules changed. OPEC spare capacity effectively fell to zero (Figure 1) and new supply became inelastic (steep part of the curve), i.e. higher prices did not lead to a ready flow of new oil since new capacity had to be built, at great expense, using expensive energy. The result was escalating prices and the spike of 2008."

That's the crossover point from peak oil at 147 a barrel, to post peak. Volatility in price will now act a braking system on the world economy. As depletion of oil, along with temporary bursts in economic activity, followed by skyrocketing oil prices, then huge drops in economic activity causing massive drops in oil price, volatility will become the EKG warning signal that our economic blood pressure is out of whack, with the heart of our industrial acitivity lurching and lunging like a train screeching to the end of the line, into obsolesence.

Live under the veil of phantom capacity, by demanding and extracting ever greater flows of liquid energy, only to awaken to an all too nightmarish reality of post peak economic collapse.

US average annual oil prices rose at about +20%/year from 1998 to 2008. In response, US demand in 2008 was back to the same level as 1999, 19.5 mbpd. However, I was struck by the number of poorer developing countries that showed increasing consumption over this time period, which was somewhat contrary to what I had been expecting. For example, Kenya's oil consumption (EIA, total liquids):

Recently, I have reviewed the net export histories of four former net exporters and 12 net exporters showing lower production (relative to a recent peak). In all 16 cases, the net export decline rate exceeded the production decline rate (or rate of increase in production in the case of China). And the former net oil exporters, plus many declining exporters, show an accelerating rate of decline in net oil exports.

One of the criticisms of the export model is that exporters would reduce their consumption in order to maintain their net exports, or in order to at least reduce the rate of decline to the same rate as, or a lower rate than, the production decline rate. These 16 case histories plus the tendency for many developing countries to show higher consumption despite higher oil prices would seem to make this scenario very unlikely.

A link to the discussion of this topic:

http://www.theoildrum.com/node/5595#comment-521884

In summary, the export model suggests that: (1) The Net Export decline rate will tend to exceed the production decline rate; (2) The Net Export Decline rate will tend to accelerate with time and (3) Net Export declines are front-end loaded, e.g., Indonesia, after hitting a final production peak in 1996, shipped 44% of their post-1996 cumulative net oil exports in just two years, in 1997 and 1998, when they shipped one percent of post-1996 cumulative net oil exports about every 17 days. Sam's modeling work suggests that the top five net oil exporters are currently shipping one percent of their post-2005 cumulative net oil exports about every 50 days or so.

And US average annual oil prices (left scale) versus combined annual net oil exports from top five (EIA):

From 1992, the initial data point on the graph, it was 13 years to 2005. 13 years after 2005 would be 2018. Sam's best case is that the top five net oil exporters will be collectively down to 15 mbpd in 2018 (his middle case is 10 mbpd).

"We got 5 years, that's all we got..."

-David Bowie.

Actually less than 10 -coupled with the graphs above this implies that the price swings are going to decrease in period, so something like $150>$$40>$150 in 5>4>3>2 years, and given the fiat currency injections the lows will be higher and the highs will be higher....

$40>$147>$40>$180>$50>$225>$62...

Just a guess...

Nick.

WT

I was thinking about your previous post with the four sample cases of ELM and the decline in exports.

I thought - what if you treat the world as one ELM country i.e. total production (I was focusing on crude only) is 74MBD. Total exports are 44MBD (according to Rembrandt)

decline rate is 5%

assume no growth in consumption

its a pretty terrifying view of projected decline in available export capacity

and I realized that when you are taking the top five exporters (in your previous analysis), you are actually focusing on the end of the tail because these countries will last the longest - so it doesn't seem so bad

its all the other countries that will cause the steep drop in the first few years.

Im reading The Prize (actually very good) and Daniel Yergin has some good observations on the 1973 oil crisis. The embargo only reduced exports about 17% - 18% globally, and yet prices went up five fold.

Consider some smaller exporters. Canada, Mexico & Venezuela are major net oil exporters, and three of the four largest sources of imported oil into the US. Their combined net exports fell from 5.0 mbpd in 2004 to 4.0 mbpd in 2008.

And as I have noted before, high flow rates can be extremely misleading, e.g., Indonesia's net exports increased in 1998, relative to 1997, so that the 1998 net export rate was only 9% below the 1996 rate, so not much to worry about? Unfortunately, by the end of 1998 they had shipped 44% of their post-1996 cumulative net oil exports.

And BTW, China is a good example of the difference between Peak Oil and Peak Exports. They went from a recent net export peak of 620,000 bpd in 1985 to net importer status in 1993, even as their production increased.

EIA total liquids for China:

Four Former Net Oil Exporters

Production & Net Export Increases/Declines Per Year, Over the Referenced Time Frame, Are Respectively Shown (EIA, Total Liquids)

China (1985-1992)

+1.8%/year (Prod.) & -16.9%/year (Net Exports)

Indonesia (1996-2003)

-3.9%/year & -28.9%/year

UK (1999-2005)

-7.8%/year & -55.7%/year

Egypt (1996-2006)

-1.7%/year & -29.3%/year

And note the increase in consumption by Egypt, especially from 1998 to 2008, as oil prices increased at about +20%/year on average:

Clearly a product of some value...

So summing up when will people/Govts 'get it' and what's going to be the likely impact??

Nick.

(When are you publishing?)

I think that Sam is going to be crunching some numbers when he gets back from a trip. I'm probably going to do something in the mean time on the 16 case histories.

Regarding the first question, I don't know, but I frequently use the "Sixth Sense" analogy, as in the movie (many ghosts don't know they are dead, and they only see what they want to see), for most Americans our auto-centric suburban way of life is dead, but we don't know it yet, and we only see what we want to see.

I know Kenya did a lot of road work between 2002 and 2006. They worked on the Nairobi-Mombasa road which had gotten really bad. I never traveled the Mombasa road, but the other roads they worked on that I did travel, went from very poor quality to American quality. I can see how this would account for some increase in petrol usage since it makes it much easier to travel. The construction itself probably consumed a lot of fuel.

Aside from that I don't know what would account for the increase, other than just a general increase in economic activity.

Egypt is shown above, and some more examples:

Brazil:

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/country/img/charts/BR_cons_large.png

China:

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/country/img/charts/CH_cons_large.png

India:

http://tonto.eia.doe.gov/country/img/charts/IN_cons_large.png

Thanks Euan,

I couldn't agree more with the supply/demand model Phil Hart so nicely described for us. I work in the commodities trading world and during the March to mid July 2008 it seems to me a portion of the crude price rise was due to large players seeking an inflation hedge on a feared weakening of the US dollar. I believe the dominant factor was however supply and demand. Does anyone have any information that can tease apart how much was due to hedging and how much of the price rise was due to supply/demand?

The hedging involves many possible sources, investors running away from shaky assets elsewhere and getting into markets to ride up that are both in short supply and the system treats as necessities. The concurrence of the same basic pattern for all commodities, points to the whole divergence of the price structure being part of a natural reaction to hitting a "stuck point" in supply responding to demand. So, I'd say if you added in all the different hedges that pushed up the price in a completely uncharacteristic way, I'd say it was 100% due to hedging.

Something that I am afraid trips up many people: The published oil industry data labeled as "demand" is not exactly the same thing as what economists would call demand on a supply and demand graph.

I have found it best to think about the oil industry "demand" as actually being "withdrawals from inventory". Production is "additions to inventory". As long as there is inventory, it is possible for "demand" to exceed production - for a while, until inventory is drained down to MOL. Similarly, it is possible for production to exceed "demand" - for a while, until storage capacity is full.

It must be understood that as the system gets close to full capacity, there is considerable pressure to move the inventory out to consumers; producers really don't want to mess around with production flow rates if they can avoid it. Thus, pricing can become exceptionally flexible on the downside when inventories are maxing out (usually when demand - real economic demand - declines). Similarly, when inventories get really tight, producers have a lot more flexibility to raise prices. Thus, I am really wondering if a depiction of the economic supply curve might be more accurately depicted as a "S" curve than as a straight line?

It must be understood from this that oil industry "demand" thus appears to be relatively inelastic. "Demand" always seems to almost exactly match production, no matter what the price, with just a little bit of differential as inventories expand or contract a bit. This is misleading, though, as I suspect that actual economic demand is far more elastic than most people have been lead to assume. When oil prices go up, consumers do indeed cut back their consumption. However, it is a pecularity of the oil industry that there are very long lead times to bring new oil into production (even in the times when there was lots of new oil to be found), which tends to force prices up even more in the short term when demand exceeds supply, and that there are also inventory capacity constraints (it takes time to build tank farms, too) that tends to force prices down even more in the short term when supply exceeds demand. These forces very powerfully keep additions to and subtractions from inventory within a relatively narrow range, and can give the misleading impression that actual economic demand itself is actually inelastic. It is not economic demand itself which is inelastic, but rather storage capacity.

A correct understanding of these particulars, I believe, will go far toward a more correct understanding of the actual dynamics of oil prices.

Excellent point. Storage levels, especially if measured in "days of supply", should mediate the strength of the coupling between end user demand, producer supply, and price in the short term.

It occurred to me as I wrote the above that one of the main difficulties in measuring this is that we have partially decoupled numbers in multiple markets that need to be sorted out, so there are multiple curve sets to work out with different characteristics.

Refiner demand <=> Producer Supply

Octane fuel demand <=> Refiner supply

Decane fuel demand <=> Refiner supply

Bunker demand <=> Refiner supply

...

All loosely coupled across different world markets by the portability and margins of the various products.

So 4 years into this experiment, there is still a huge amount of analysis to do.

Put simply, demand is inelastic in that it does not vary much owing to price variations alone - we still drive our cars even though it gets more expensive to do so.

Put simply, you're wrong.

from 2008:

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122728664289448183.html

The good news is that gasoline consumption has fallen compared with a year earlier in every month from March through September of this year, according to data from the Energy Information Administration. Vehicle miles traveled -- the wonky term for how much we drive -- have dropped for 11 straight months, and fell 4.4% in September, according to the Department of Transportation.

OK - the demand curves do have a gradient that shows demand will be curbed by high price. The demand curves are schematic since we don't really know how global demand is affected by price.

The lowering of VMT will be in part due to high price but perhaps in greater part due to rising unemployment.

high prices or unemployment doesn't matter to the barrel of oil not used. The point is, people DID drive less when the prices spiked.

There was also an article in the SF Examiner about 2 years ago talking about how the rural poor in northern california were radically trimming back their driving and having a hard time finding suitable vehicles: cheap cars that are good on gas but can clamber through the dirt and gravel roads. this is exacerbated by the retirees and second-home owners who have money to burn (compared to the locals).

What is also not part of your discussion are the limitations on short selling that have been installed to curb speculation on oil.

Mind telling us about these limitations on short selling to curb speculation on oil Stuart? Short selling is a term used in the stock market, not the commodities market. Sure, every futures contract has a long and a short side. But no limitations have been placed here whatsoever.

And as far as the stock market goes there is some talk of re-instituting the uptick rule but so far no action has been taken. SEC Weighs New Short-Selling Rules But again, this has absolutely nothing to do with the futures market.

Don't forget Stu, the futures market and the stock market, or equities market, are two entirely different things. In the futures market you can hold the short end of a contract but there is no such thing as short selling. Short selling is selling stock that you don't really own. You borrow it from your broker. You must repurchase it later and return it to your broker. Also there is such a thing as naked short selling, selling stock you don't own and don't borrow either. That is already against the SEC regulations but some still do it. They are cracking down on that however.

Ron P.

Demand elasticity has a time dimension. People can make more energy-reducing decisions for the long term than for the short term. If oil prices spike they can't immediatey change their job, move, or buy a more efficient car. All those changes take time and money to execute. Current oil prices are causing long term behavioral changes. The fear of another spike is also causing long term behavioral changes. Oil demand will decline in Western countries as a result.

Look at US oil consumption in the early 1980s. People got the message and for year after year oil consumption declined even as oil prices declined.

We are headed for further Western consumption declines even as demand grows in oil exporters, China, and India.

While the US consumption of gasoline dropped in 2008 to a level not seen since 2003, the daily average supply has been 9105, 9159, 9253, 9286 and 8989 thousand barrels per day from 2004-2008 inclusive. The consumption in 2008 is 98% of the 5-year average and 96.8% of the 2007 consumption. Consumption since May 2009 has been just about the same or slightly higher than their equivalent 2008 counterparts as reported by the weekly petroleum review.

That hardly constitutes elasticity. Now, if the consumption had dropped, say, 10-15% from the medium term average or from the previous year, then we might say that the conclusion about consumption/demand being inelastic is wrong.

Here's the reddit & digg links for this post (we appreciate your helping us spread our work around, both in this post and any of our other work...):

http://www.reddit.com/r/reddit.com/comments/947qc/oil_price_where_next/

http://www.reddit.com/r/energy/comments/947q2/oil_price_where_next/

http://www.reddit.com/r/collapse/comments/947q5/oil_price_where_next/

http://www.reddit.com/r/environment/comments/947q8/oil_price_where_next/

http://www.reddit.com/r/Economics/comments/947qa/oil_price_where_next/

Find us on twitter:

http://twitter.com/theoildrum

http://friendfeed.com/theoildrum

Find us on facebook and linkedin as well:

http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=14778313964

http://www.linkedin.com/groups?gid=138274&trk=hb_side_g

Thanks again. Feel free to submit things yourself using the share this button on our articles as well to places like stumbleupon or other link farms.

Would it be useful or even possible to add a supply curve and a demand line to Fig. 5 showing the 2008 peak price intersection?

JB

I love this post!

I tried making some graphs of oil production and price a while ago. What a path the point has taken! IMO there are a few really important conclusions we can obtain from this:

a.) It is amazing how much oil production DOES follow the laws of economics, whereas with the price drop in early 2009, production fell back almost exactly to pre-2008 production levels. Obviously production is responding to the price signal. That shows very clearly that oil production is a monotonically increasing function of price.

b.) It is amazing how much oil production DOES NOT follow the economics, whereas the flexibility of supply is almost nothing. A 75% change is price corresponds to a 5% change in production. This is the ultimate "oh s@*#" realization.

This is a matter of supply and demand, but it is more so a matter of price sensitivity. Price sensitivity is the fundamental assumption behind supply and demand, and well... economics itself. The problem IMO is point b. Lately, people have been talking about "the death of Economics", economics being wrong, and so on and so fourth. I intend to argue that one way or another, the behavior of the oil markets is showing that something is terribly terribly wrong with how economics plays out in the real world.

True, we hit physical production limits. Ok, I'll give you that. But what about the backside of that? The oil production system demonstrated not only the inability to increase production, but also the inability to curtail production. Economics, and society itself, isn't configured to factor in the concept of depletion. That makes no sense and that is why economics is broken. You could refine the concept of saving to include the concept of depletion and effectively the capital stored in oil - the saving power of oil left in the ground. The problem is that no company and no form of economics is effectively factoring this in. Not only did economics fail to include this into the fundamental supply and demand model, but Exxon failed to include it in its business model.

You'll notice that if you separate OPEC and non-OPEC oil production, almost all of the changes come from OPEC production. They are the only nations in the world apparently concerned with preserving oil-in-the-ground value, albeit only to a small extent. The ultimate fallacy of our world is thinking that the price of oil should be proportional to the marginal cost of extraction. It should not, but it is. When the price of oil was $35 per barrel, those with extraction costs of $5 should have stopped all production and written future contracts far enough out to satisfy their discount rate. But instead, those fields continued to pump world oil storage full and further exasperate the contango stalemate.

Those who decrease production by 5% with a 75% change in price signal are diluted numskulls. They are throwing economics to the wind and destroying investor value.

That's the other assumption of economics that has been broken: people act rationally. Our current use of oil is not rational. The premium for saving our natural petroleum riches for a rainy day is almost zero.

This is why I believe that the graphs above show that accurate economic models are not applicable to our society. And the reason is simple - we're kidding ourselves about the physical reality of our society.

I am a geologist, not an economist. I was very surprised plotting the data to see how simple the story is - I'm used to working with complexity. I think economics and our market system are alive and well. It's not possible to avoid seeing that the industries that are being hit the hardest are automobiles, airlines, house builders - all energy intensive. And the laws of supply, demand and price seem to be alive and well - its just that the relationship is exponential and not linear.

The media don't help in reporting daily / weekly movements in oil price related to "trivial" events - waiting for inventory news, insignificant pipeline in Nigeria blown up, expectations of hurricanes in the Gulf and most of all speculators driving the price. All this is captured by the noise in the data, while the overall structure is controlled by supply and demand.

Politicians are also doing untold harm by having their heads in the clouds and promoting that low energy prices are good. A year ago they were doing everything they could to get energy prices down - they certainly succeeded.

I'm more on the finance side of things. I don't know much about the geologic situation other than what I read here... but believe me, I get as much of the geologic picture as I need to. None of this is rocket science, or even difficult for that matter.

I completely agree. Worldwide human society is a very complex system. But yet oil production has very clearly followed the trend in Fig 2 - so simple you could teach to a middle school class. Inasmuch as economics predicts that price will be the marginal production cost, the data has hit the bulls eye.

Of course, my claims contend that people should wake up and realize that this is not a good pricing system for oil, requiring a more complicated game-theory type of model, but even the largest company in the world has apparently not advanced to this level of thought. For them it's "pump pump pump as long as there's a profit".

The mainstream thought on this matter would likely ostracize you and I along with the speculators because our analysis of the situation concludes in higher pricing.

But yet speculators could avert a serious crisis. An individual could buy a futures contract a few years out, and by economic theory, the system should work itself out. The producers should respond to that signal and take production offline. I don't think we ever see this. You can get a 30% annualized return right now by storing oil until the next month. And help save the world as a bonus!

http://finance.yahoo.com/q/fc?s=CLU09.NYM

But this doesn't happen due to a single real world factor: human stupidity. For one, USO and other funds only buy front month contracts, meaning that the majority of speculation does no production work in terms of intelligent resource allocating. Second, companies need to have access to that ever-important ability to either curtail production or store oil. They don't.

I look at storage as a 2 to 3 month "half life" in the price signal. The price can be whatever it feels like today, but by 3 months from now it must reflect genuine supply and demand. We need a longer half life, IMO. That pretty much sums up my thoughts on the matter.

----

I might disagree that politicians succeeded in getting oil prices down. The run up and fall in 2008 was "feeling" the edge of the economic oil cliff. The consistency in the data suggests that the driving factors are much bigger than any of us. The scale of this phenomena is something that no single institution can hope to match.

You've said it in a very clear and concise way, our steering mechanism is following a path a bit different from the physical world, which has been the problem all along.

"Those who decrease production by 5% with a 75% change in price signal are diluted numskulls."

Love it; would do Norm Crosby proud. ;)

I feel compelled to repost my previous thought.

The price of oil is substantially going to depend on supply.

We have very little information regarding the supply capacity of OPEC, which is the critical supplier.

ERGO - We are unable to account for the supply capacity for a critical portion of the oil supplying world.

ERGO - Price estimation is not wild guessing, but it's not too far from it.

Let me tour the KSA and see live production data, then ask me about price.

Two points: (1) Average annual US oil prices increased from $57 in 2005 to $100 in 2008 and (2) Saudi net exports were down for three straight years relative to their 2005 rate.

The only number that really counts to oil importers is the volume of (net) oil exports delivered to the market, and if Saudi Arabia had maintained their 2005 net export rate, they would have (net) exported 10.0 Gb from 2006-2008, inclusive. The actual volume was 9.1 Gb (EIA), a shortfall of 900,000 mb.

I think that 2005 was probably the final Saudi production peak, and I could of course be wrong, but I think that it is extremely unlikely that they will ever again match or exceed their 2005 net export rate of 9.1 mbpd.

Although all the pieces are there, the author fails to arrive at the correct conclusion.

He is incorrect in his argument that a "plateau supply of 84 to 88 mmbpd are secure for a couple of years," primarily because he completely fails to realize and isolate the impact that the exponentially growing Chinese economy had on the 2008 oil price spike due to their massive demand for oil, as well as the likely effect a revitalized Chinese economy would have on an OECD world already weakened by recession and which will not recover for the foreseeable future.

Although the author does insert a caveat about the global banking system surviving and the global economy resuming growth in 2010, he doesn't seem to understand the full implications of that caveat, which undercuts his entire argument. The Chinese economy is already ramping up in 2009 and the global banking system has indeed survived the current crisis and is expanding rapidly, providing plenty of capital to feed the enormous demand of the Chinese market.

He also incorrectly states that there is a limit to the oil price the global economy can bear, when it is actually China that will set the global price of oil by its demand and economic power. It is only the OECD countries (especially the US) that will experience a limit to the oil price that our economies can bear.

Finally, he argues that as a result, “any new price spike, as the name suggests, will be short lived as high prices kill demand and we are likely to see a repeat performance of the 2008 crisis." However, when oil spikes again they will not drop (even now the price is still hovering around $70.00 bbl - it did not drop back down to any kind of "normal" price as it did after the 1970's oil price spike), but find a new global equilibrium price determined solely by Chinese demand and control of natural resources worldwide that we cannot afford, and the US economy will crash hard into Great Depression II.

Gordon is not a common Chinese name.

;-)

Meaning what, exactly?

I interpret it as meaning he is sceptical of the claims about Chinese recovery, but does not have the time or means to challenge them. My own search failed to find any info particularly proving anything other than that the Chinese govt has done a stimulus package (which will perhaps give a few more months' illusion of success before the down returns).

Thanks for the interpretation, RobinPC, but I knew exactly what Nate meant.

He was being dismissive and patronizing, as in “who do you think you are to have an opinion that counts in my world?”

If he does not have the time or means to challenge me, then perhaps it would be better not to take cheap shots either.

If you or Nate can’t find anything other than the fact the Chinese government has provided a stimulus package to their economy (one that actually seems to be working to provide needed stimulus, as opposed to the joke we have), perhaps you should change news sources.

This will likely be my last comment on TOD for some time, but I seem to have offended you, a new user, so I will delay my departure to answer your comment. Re the Gordon/Chinese comment, I was being flip - you had just signed up and defended China as the future Conan of world growth and it seemed sort of funny.

1)The built capacity in China is designed to be a world exporter of products, not as an import substitution structure. China has major water issues, it is much more efficient for them to import soybeans and grains then use that water indirectly on food - they will be massive food importers for many years to come - in the end food (and oil) are more important than electronics and low utility consumer goods (as a generality)

2)China recently has had several failed treasury auctions. While this also has (negative) implications for US treasury auctions, it highlights the fact that their money supply has been growing in double digits, and the yuan is also a fiat currency (fiat being latin for 'faith'). Faith in a pseudo-communist government backs their currency, just as faith in our government backs ours. IMO, all fiat currencies in a global economic system are joined at the hip in the end.

3)As such, I am of the opinion there is no way China can have a viable thriving economy if the rest of OECD is in throes of depression. This current crisis will/must end with the renegotiation of credit or the issuance of a new global currency, of which China would likely play a role. Less likely, but possible is a major war (and US still has first strike capability vs ROW, a fact they use in foreign policy discussions as a matter of fact threat, not with intent to use.)

4)

That is a little strong, but is part of the reason I am taking a break here- it is difficult to rehash discussions with new folks on old topics over and over. I've not talked about China much on this site and your opinions on it may well be correct, though for the reasons above I disagree. If you took that comment as an insult, it was not intended as such and I apologize.

5)My opinion is that the 'economic empire' (basically capitalism), will borrow from all areas possible (foreign countries, new rules, public coffers, the future, thin air, etc.) to put off the reckoning that is due from disconnect of real vs abstract capital. As such, even though we are well into collapse, it won't appear like it until 11:59 pm metaphorically speaking. China is in bed with all the rest of us. If they somehow had Russias energy endowment, ample fresh water resources, a lower population density, and had a healthy environment, and they had built infrastructure specifically to account for a non-export reliant economy (no country has), then I would agree with you. It is possible that this all shakes out with an all out war between China and US - I think this is more plausible than China as world economic power and US in the tubes. In any case, I speak Mandarin and still have friends in high places in Beijing and count this as an insurance policy -I'd be a good candidate for foreman/translator if you end up being right...;-)

Just my 2 cents. Good luck Gordon.

Neil,

Thank you for taking the time to respond properly. The tone of your reply still leaves something to be desired, but “apology accepted” nevertheless.

Although I am a “new user” to your website, that fact alone has nothing to do with the relevance or the quality of my opinion about China. In reality, I have been following “The Oil Drum”, which I consider to be a somewhat narrow and biased but relatively useful news source, for a long time and am thoroughly familiar with the issues and views expressed on the website, as well as the background of many of the personalities contributing to the website. I have just never felt compelled to contribute to the discussion before.

To reply to your comments (unfortunately, I really must provide some background information in order to sustain my conclusions at the end, so please bear with me):

The Chinese economy was designed to be a world exporter of goods, just as you say, but the unexpected collapse of Capitalism in the OECD countries has forced them to become more self-sufficient, which is what China had intended all along, just not this soon. They are irritated at the US because they failed to properly take into consideration the fact that Capitalism in the US would fail so prematurely, so that they have a far larger investment in US dollars than they intended to have eventually. Their goal is to become the next world super-power. Anyone who doubts that fact is deluding themselves.

Their current intensive drive to secure natural resources around the world should be ample evidence of their intent. The Chinese leadership knows that there are not enough natural resources left in the world for them to achieve a standard of living anywhere near that of the OECD, and they intend to “lock up” (by whatever means) what is left of those resources for themselves as soon as possible. This is the threat the OECD countries must eventually face: the stark reality of 20% of the world’s population (historically pillaged and demeaned by the rise of the Western European powers) demanding, by military force or economic manipulation of the market system, their "fair share" of what is left of the world’s resources after the OECD countries have decimated and squandered them.

The Chinese rise to power began roughly around 1980 when the new progressive Chinese leadership came to power. Since then they have been systematically bleeding the OECD economies for their benefit in order to “jump-start” their economy, much as Japan did in the late 20th century. Even though China is often portrayed in the US media as moving toward or becoming a Capitalist nation (an arrogant notion of the wealthy class that the Chinese prefer not to dispute for their own reasons), they are steadily morphing from a Communist central controlled economy to what is now obviously a Mercantilist society. I wouldn’t hazard a guess at what they will eventually become because it depends on how the government and rising economic power of the social classes interact with each other in the future. The methodology they have been and are using to acquire, first economic and then military power, is really quite clever (the Chinese should rightly be proud of this accomplishment). They are using the natural greed of the OECD (especially those in the US) wealthy as a weapon against us. In other words, they are beating us at our own game.

The “fall” of Russian communism was an unexpected boon to China in that the US was free of cold war competition and could concentrate on expanding US trade in China, the “Holy Grail” of western trade for centuries. This fact unexpectedly allowed the Chinese economy to start growing exponentially with double-digit gains year after year, which brings us to where we are now. Recent developments in the US stock market indicate that the wealthy have “come off the sidelines” and are beginning to invest heavily in the Chinese economy again (there’s really nothing else left to invest in, now that the wealthy class has destroyed the Capitalist system through their insatiable greed). They believe the Chinese economic package is working, which by any means of reckoning it is, and are doing their level best to get access to that golden market without delay to beat others to the trough, so to speak.

I don’t know if China will be able to successfully “decouple” from the OECD countries, especially the US, but they seem to be making remarkable progress in that direction, far more than I would have ever thought possible in such a short time. If they are indeed successful, and I can’t see any reason why they wouldn’t be for a multitude of reasons, it would mean that your opinion that “there is no way China can have a viable thriving economy if the rest of OECD is in the throes of depression” is somewhat off the mark. Don’t get me wrong, I hope you are right because none of the alternative scenarios are good for the OECD (especially the US) countries, to say the least.

Yes, I agree with you on the following points: (1) that the “economic empire (basically Capitalism), will borrow from all areas possible to put off the reckoning that is due,” (2) that the US dollar is in its final death throes and will shortly be supplanted by some new global currency, probably the Yuan, and (3) that China has an incredible deficit of natural resources and infrastructure problems to overcome to match the economic power of the US, but the Chinese people have proven they are patient and resilient, perhaps most importantly they plan for events over the long haul, unlike the US which can’t seem to remember anything beyond the last “Survivor” winner on government-controlled TV.

No, I disagree with you on the following points: (1) China WAS in bed with the rest of us, but I think the recent strides they are making to improve their domestic economy and to reach out the other Asian nations to create a more “localized” or “selectively global” trading network (as in the artificially created Wall Street BRIC notion) prove that they won’t be “in bed” with the OECD much longer, or at least not on any terms we would like. (2) You said that “if they somehow had Russia’s energy endowment” that you would agree with me. Well, perhaps you should check on the current status of Russian-Chinese relations. In case you hadn’t heard, the cold war is over. They are presently holding joint military exercises (for internal security and to protect against terrorism, of course), are in the process of carving up Central Asian resources (the “stans”) for their mutual benefit, and are in the process of completing massive trade agreements between their two countries (that have historically been rivals and often bitter enemies). (3) As to the US having “first strike capability,” that is true, and ordinarily I would agree with you that China would be foolish to gamble that we don’t have the “stomach” to use them if push came to shove. However, with the recently developing close ties between Russia and China, I must disagree because it will soon become apparent that we are no longer dealing with China alone, but with a coalition of "Russia-China," whose combined military might (remember that Russia still have a formidable arsenal of ICBM’s ready for launch) could give us pause before we summarily “push the button” to punish a disobedient China. (I’m afraid that most people in the US have a really antiquated view of China and the Chinese people that doesn’t fit the present reality, which I am sure you are well aware of.) This is a completely new development in US-China relations that fundamentally alters both the geopolitical and economic environment of the world we live in, and so far at least, we seem to be completely oblivious to it. The “Great Game” continues, perhaps in its final installment, but the US will not be around to find out or care who wins. We will have been eliminated long before that, just as the Great Powers of Europe were destroyed previously, but perhaps not with as good an effect. I’m afraid our lot will likely be much worse this time around. There is a real hatred of the US economic juggernaut in the world today, not without ample reason, and we may not be allowed to simply collapse of our own greed as others have before us.

I could go on, but hopefully by this time you understand my objection to Mr. Mearns' conclusions. The “weighted effect” of the Chinese economy must be specifically and explicitly included in any analysis of “peak oil” or the conclusions are simply wrong.

I apologize for the length of this response and beg your indulgence for that fact. I agree with you that, “it is difficult to rehash discussions with new folks on old topics over and over.”

I want you to understand that I fervently hope you are right in your analysis. However, nothing you have said, nor anything that I have researched on this subject, even remotely leads me to the same conclusions as yours.