World Oil Exports [00] Introduction

Posted by Luis de Sousa on June 27, 2008 - 9:55am in The Oil Drum: Europe

History

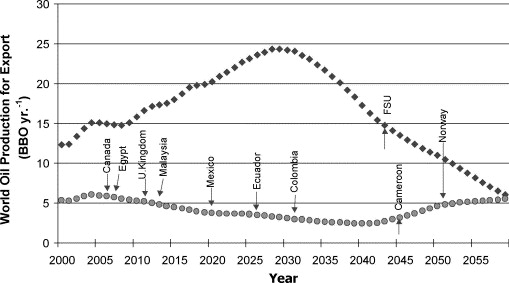

Probably the earliest assessment of future oil exports on a worldwide level was that authored by John Halloc et al., entitled Forecasting the limits to the availability and diversity of global conventional oil supply published by the Energy magazine in 2004. In spite of being produced before the first oil price rises of 2004, this work has the merit of going beyond the traditional Hubbertian analysis of oil supply. The authors found not only that the volume of oil available to the market will follow a dynamic of its own, declining faster than total production, but also that the number of exporting countries would diminish, compromising the diversity of supply.

Figure 1 – Conventional oil production available for export according to Halloc et al. (2004). Diamonds represent net exports from FSU, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Nigeria, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, dots exports from the rest of the world. Arrows show forecast moments in time when producing countries cease exporting oil. Click for article.

Later, prices would start increasing in the wake of vanishing spare capacity in the Middle East. The accelerating flow of events fostered communication through faster means, overriding the slow processes of traditional submission, peer review and printing. The internet became quite alight with resource depletion news sites, fora and weblogs, were the idea of a singular concept of oil exports would be pursued.

Early in 2006 Jeffery Brown laid down the idea of “Export Land”, a model where an oil exporter faces both a decline in production and an increase in internal consumption. He observed that the world's top three oil exporters were facing similar conditions. Then, together with Khebab, further analysis would be produced reaching similar conclusions for the top four oil exporters. The latest update to the Export Land Model resulted in the following forecast:

Figure 2 – The Export Land Model for the top five oil exporters. Click for article.

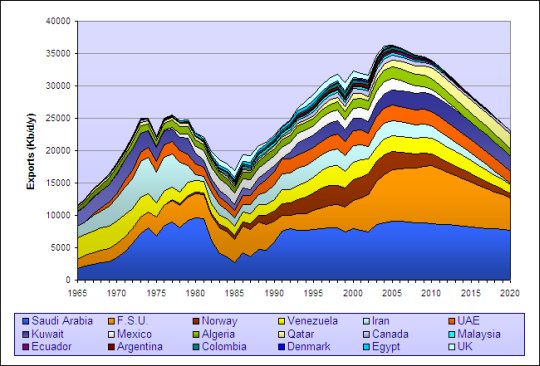

In 2006 The Oil Drum would harbour the first version of World Oil Exports (WOE) a country by country forecast of future export volumes up to 2020. Although a simple accounting exercise, based upon rudimentary forecast tools, the outcome would give another dimension to the international oil market's future. Exports were peaking (possibly already in decline since 2005) and where in for a decline at an accelerating rate. After an update later in 2006, the picture devised was the following:

Figure 3 – The main graph produced by WOE 2006. Click for article.

WOE 2006 lacked some important countries for which data on consumption wasn't satisfactory at the time: Angola, Iraq, Libya and Nigeria, together with a large number of small exporters. WOE 2006 missed almost 20% of the international oil market.

In large part due to the continuous efforts of Jeffrey Brown, the concept of an unfolding decline in the volumes of oil available for international trade slowly reached larger audiences. CIBC economist Jeff Rubin would embrace the concept as a reason to invest in North America's unconventional oil resources, eventually bringing it to main stream media.

With oil prices doubling in less than one year, a broader conscientiousness has yet to be built of a real shortage of oil flowing to the market. Public cries of market speculation or manipulation, geopolitics and above ground factors in general as being the main drivers of current high oil prices continue to be the norm, in spite of stark export numbers. It is therefore due time for a new WOE assessment.

Concept

The present world oil market can be perceived vividly in this graph published by Kenneth Deffeyes:

Figure 4 – The Supply vs Demand plane compiled by Kenneth Deffeyes. Click for article.

The crude oil Supply curve is getting vertical with elasticity virtually at zero. But with oil prices climbing from 40$ a barrel in 2005 to a record of 139$, so far, in 2008, Demand stood still. Importers have no short term answers to supply constraints and keep bidding higher prices. It is a market were Supply rules.

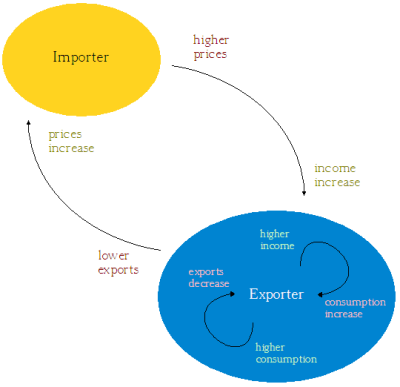

This price increase represents an enormous wealth transfer from oil importers to oil exporting countries, as calculated by Kenneth Deffeyes now summing up to several points of the world's GDP. In its turn, this new found wealth in exporting countries will foster higher consumption internally, leaving a shorter fraction of production available for export. Population in exporting countries tends to grow, along with consumption patterns (if not for everyone at least for some section of society) with access to technologies that provide a better quality of life but invariably consuming more energy (cars, homes, home appliances, air conditioning, etc). This is the basic dynamics behind the oil exports model.

Figure 5 - A simplified scheme of the dynamics behind the WOE model. Click to enlarge.

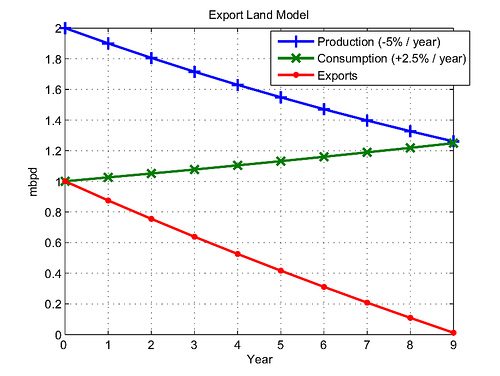

The main change from a sufficiently supplied market is for mature exporters facing terminal declining production. Rising prices offset an otherwise declining income, and if the production decline rate is lower than the price increase rate that income will actually rise. In such environment oil exporting countries find little incentive to either try increase production or curb internal demand. Production and internal consumption run towards each other, rapidly swallowing exports. Jeffrey Brown and Khebab captured this effect on the following graph.

Figure 6 – The Export Land Model. Click for article.

Criticism

These concepts have received some criticism, that can't be dismissed upfront. Two main aspects must be addressed, first oil importing countries cannot bid ever higher oil prices continuously, and secondly at some point, when exports dwindle below a certain threshold that start hurting the exporting country's economy, action should be expected. While these observations seem prescient, up to now events are not unfolding that way. It is worth understanding why.

Oil demand has kept healthy for several reasons, lack of alternatives (especially on Transport) and subsidized consumption in some countries are perhaps two of the most important. In the short term the most likely factor to curb world oil demand is economic recession (for which a change in current loose monetary policies might be a catalyst). But this recession may not be effective worldwide (or it may affect only certain economic sectors). Moreover, an economic recession that would induce a retraction of demand would effectively reduce world oil exports, possibly at a faster rate than that envisioned now.

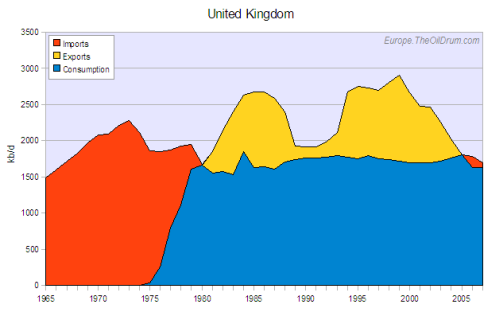

On the exporters side there are two very interesting cases of countries that turned net importers just recently, the UK and Indonesia. Although two markedly different countries in economic terms (one developed, another developing) both show similar patterns of internal consumption and production fast running to each other without any action taken to avoid the rendez-vous.

In Indonesia action to curb internal demand was only taken several months after exports sunk to zero, with subsidies on oil products reduced just recently.

Figure 7 – Indonesia Oil production and imports. Red: imports; blue: indegenous oil consumed; yellow: exports. Click to enlarge.

In the UK any visible action to change the situation is yet to be seen. Government is just leaving to high fuel prices the task of curbing demand, facing at the same time a wide budget deficit opening ahead.

Figure 8 – UK Oil production and imports. Red: imports; blue: indigenous oil consumed; yellow: exports. Click to enlarge.

Both countries also share the unavoidable effects of terminal oil decline. The option to increase production is left out, and governments seem unwilling to take unpopular measures towards energy efficiency.

Methodology

Despite the weaknesses identified, the main objective of the present update is to complete WOE, assessing the countries up to now left aside. Still some improvements will be tried.

The main data sources used are:

- ASPOs Newsletters edited by Colin Campbell;

- BP's Statistical Review of World Energy;

- EIA's country by country Energy Profiles;

- Oil Megaprojects database;

- United Nations Population Forecasts;

Production

The model will continue to rely on Colin Campbell's thorough country by country assessments published monthly in ASPO's newsletter. While the forecasts contained there were the only ones considered in the 2006 version, this time other projections will be analysed (if existent) and curve fitting methods employed whenever practical. These will also be cross checked with the data gathered by the Oil Megraprojects database.

Consumption

This is where the model will hopefully get better improvements. Instead of searching for consumption increase patterns in plain consumption values, this time the past evolution of consumption per capita will be the model's main driver. For many countries a long-term trend emerges on oil consumption per capita; in such case consumption forecast resumes to an exercise of population growth for which the UN provides worldwide public data.

Objectives

World Oil Exports doesn't aim to be an accurate picture of the future, it is a possible picture. No error bars are given or alternative cases, first for the number of countries is such that gathering each one with alternative cases in one graph would be near to impossible and secondly because WOE pretends to present just the most likely path and not all or several possible paths.

The final outcome of WOE aims to be a guide for policy makers and stakeholders in general from oil importing countries. It will show from which countries oil will likely be available in the future and in which quantities. Hopefully it will help them prepare in advance for the challenges to come.

WOE will provide a macroscopic view of the present and future world oil market, hence care should be taken when relying too heavily on it for individual country assessments (although all effort will be taken to produce a clear picture). Deeper assessments on individual countries are both welcome and encouraged.

Format

This time, instead of an extended article, WOE will be a series of articles, of which this one is the first. Subsequent articles will deal individually with each country. This will both provide for a more comprehensive assessment and enforce it as an open, ongoing work. At the end of each country assessment the main macroscopic graphs will be updated.

Luís de Sousa

The Oil Drum : Europe

Very good work, and as I noted in our prior work, I was building on prior work by Simmons & Deffeyes, based on Khebab's excellent technical work.

In my opinion, declining net oil exports should be the #1 story in the world, and we need to be implementing emergency electrification of transportation programs, combined with a crash windpower program and a big push for more local, organic food production.

As Alan Drake has pointed out, if we could do electric transportation 100 years ago in West Central Texas, with minimal oil input, why can't we do it in 2008?

San Angelo, Texas, Circa 1908

http://www.energybulletin.net/14492.html

Electrification of Transportation (Alan Drake)

http://www.energybulletin.net/5673.html

Published on 22 Jul 2004 by San Francisco Chronicle. Archived on 25 Apr 2005.

Berkeley: Urban farmers produce nearly all their food with a sustainable garden in their backyard

I'm all for electric transportation, but we should focus most immediately on reducing waste in the current system. It seems that cutting driving speeds could potentially reduce gas use in half, though the speed reductions are drastic. Government assistance for growing food at home are harldy in the public eye. There is much waste which could be cut out of the system right now, and that would buy us time. Educating the public, especially on a global scale, takes leadership. Let's game extra time out of the current system while we bring new technologies to market.

Tell everyone you know who might possibly be able to, to ask to telecommute

You can't just fight alligators, though, you have to start draining the swamp. The Hirsch report says at least 10 years is required for even an "Apollo Mission" level of effort by government, industry, and citizens. Hence, the beginning of a dramatic push to restructure our transportation system cannot be put off.

Jeffery! You and your ELM is described in the biggest Swedish Industrial Daily "Dagens Industri" today. You find the paper here www.di.se, but the article is not online.

The articles headline is "Därför stiger oljepriset" which translates into "This is the reasons for escalating oil prices"

The ELM is given centre stage for the explanation of rising oil prices and your calculation that Mexico will be net importer by 2014 is quoted as well as that the Saudis might consume 4,6 mbd in 2020. A funny thing is that “Peak oil” is not mentioned at all. Maybe the economic nature of ELM is easier to grasp for an economist, rather than the geological reasons for “Peak oil”´.

Rgs / Olle

Thanks for the story. The irony is that my local paper, The Dallas Morning News, is (mostly) still pretending that the net export decline is not newsworthy.

Wow! Thanks for this piece of news, Olle! Can you translate key parts of the article (I don't get the paper version of DI)?

This may be small thing for others and may be easily lost in this summer season news, but I think it is big for us Swedes and Finns. DI is followed closely by business people here in Finland as well, so some of the more hard-headed bozos who's heads I've been trying to turn will now start to make a bit more notice.

It really is quite funny, if it weren't so sad at the same time.

We can have the exact same data and often more thorough analysis, but they don't believe us. But once it's in DI/KL/WSJ/FT/name-your-paper-here, it becomes the truth - regardless of the solidity of the data or reasoning.

But I'm glad it's happening. This will really help in trying to tell the companies what they can do. Ignoring the fundamentals is not a wise choice for many a business.

In fact, I just came from a meeting with a very sharp and open-minded CEO, to whom I gave the overall PO pitch a year ago. This year, after rising transportation costs, spiraling oil price and combined crunch in financial and agri-comms sectors, he's ready to act. Unfortunately he's clearly in the heatseeker category. The rest will follow with a 2-5 year lag based on my previous experience with such trends. They are totally in a reactive and temporal damage control mode. They think this is a passing trend. By the time they may have changed their mind, it may well be way too late for many of them.

So if you're investing in companies, start making note which of them are peak oil aware and actually acting on it.

I can mail you the scanned article if I get your e-mail address.

Rgs / Olle

What a feeling it must have been to enjoy public transportation in West Central Texas and many other parts that were electrified in 1908. I think that it will be easy to re-electrify them in the future, although I have concerns about our grid's capacity. Technical and capacity challenges aside I believe that this will be the among the many public works projects undertaken during the coming transformation. (Is that the new euphemism for greater depression?)

One thing is clear though; the age of the automobile is probably over. Simply doing the math indicates that there just isn't enough time to accomplish a seamless replacement of the fleet in the U.S. There are currently 300 million registered automobiles in the U.S. Toyota just sold their millionth Prius hybrid after eight years. While they are ramping up to one million a year by 2010 even replacement of one third of the U.S. fleet would take 100 years from now.

No doubt other manufacturers will step in, and produce fully electric cars for mass market consumption in the near future, however we are still up against a resource problem. I suspect that there simply isn't enough time and energy available either.

Being optimistic I believe that human ingenuity will save us through combinations of massive conservation through re-use, lifestyle changes and replacement of the automobile with public transportation and electric scooters and bicycles. The transformation will be difficult for those that are most attached to the current paradigm.

Hi Occitan,

Just think a minute, in 1908 what was the per capita electricity production capacity in US?, I would guess only a fraction of the 11,000 kwh today. Now that allows a lot of todays electricity to be diverted for trams, electric cars etc. Most developed countries do quiet well with annual 4,000 to 8,000 kwh/ per capita.

In the US 15 million new vehicles are sold per year and 50% of VMT is done by vehicles aged 6 years or less. By 2010 there may be less than 1million hybrids sold in US, but many other vehicles having much higher fuel economy than existing new cars(25-27mpg) could be sold, and if gasoline stays above $4 a gallon will be sold. SO in 6 years we could have 50% of VMT by vehicles perhaps having 50% or possibly having 100% better fuel economy than todays new vehicles. your assumption that it would take 100 years to replace entire vehicle fleet with hybrids is assuming that the maximum production of hybrids will never exceed 7% of market. If think even GM completely changes it's production in less than 20years( look at how quickly SUVs and light trucks went from 10% of fleet to >50%). At the rate of new SUVs sales could see SUV and light trucks back to 10% of new fleet in a few years. Since this segment has 22mpg average fuel use, if these were replaced by 44 mpg vehicles, very substantial reductions in gasoline use would be possible.

If you look at traffic on weekends, its obvious that a lot of VMT are not essential for work or for the productive part of the economy, but are for shopping, entertainment,recreation. If prices continue to rise to say $8 a gallon( European prices) or even higher, 2 car families will use the more fuel efficient vehicle more often, a even cut back on some driving.We will probably see an increase in mass-transit use.

I like the idea of mass-transit but its just not going to happen very quickly because of the very high capital costs, the way cities have been built since 1945 and great increases in taxes needed. Much easier to convince US (and Australian) public to buy new plug-in hybrids and hybrids and save a bundle on gasoline, keep the suburbia dream, add a little insulation to homes, replace incandescent bulbs with more efficient lights and a few other token conservation measures .

Car sales are dropping rapidly not just SUV your making a big assumption that people will be able to buy cars at the rate they did in the past.

Given that we will be at least in a prolonged recession.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/19/business/19charts.html?partner=rssnyt&...

Probably a depression. In any case fleet replacement in this never ending recession will take longer than 10 years. Next of course the value of the older gas guzzler will drop rapidly in general the car owner would have to bring a lot of money to the table to pay off his old car loan and get the new one. And of course he has to remain credit worthy to even get the loan.

Yet again people that see a bright future focus on one or two things and ignore the entire problem.

Start first with understanding that long term loans for cars and homes etc was based on fiat currencies and the ability to inflate away part of the debt version to prevent default. This was driven by cheap oil and commodities so the government could inflate without causing commodity price inflation. Without cheap oil/commodities if the inflate it just raises the prices of critically needed items such as food so purchasing power drops.

The beast cannot be saved.

memmel,

Thats an interesting graph because in the 1978-85 period when car sales($ value or number?) declined is when vehicle fleet mpg increased the fastest in the last 50 years. If you think about it, most fuel efficient cars( except HEV's) are much less expensive. I am not sure about prices in US or Europe, but in Australia, smaller cars using 6L/100km cost about $AUD 15,000, while SUV's and light trucks getting 9-14L/100km, are about $AUD 35,000 or more. In other words a family could rather than buy a new SUV, replace both fuel inefficient cars with two new cars, use about half as much fuel for each car and still spend less. If its not happening yet in US, wait until prices are >$8 per gallon. Just about every new-car buyer can do the sums( small car=saving >250 gallons of fuel per year, plus half the financing costs).

Its more complex for second-hand car buyers, but if you look in papers lots of older fuel efficient cars available <$5,000.

The issue about paying off existing cars is important, but many new cars are on 3 year lease arrangements. Its not as though consumers are spending 100% of disposable income on vehicles. In The Australia Financial Review it showed a graph that shows that vehicle running costs as % income are only 6%( was 8% in 1980). Even a further doubling in fuel( to $3.50/L;$USD 12/gallon) could be accommodated by reductions in eating out, reductions in electrical, furniture and white goods purchases.

Excellent article. The author would benefit from some editing/proofreading help.

Maybe you can offer your help? This is all volunteer work. Many people don't speak English as their native (or even second) language. All help is probably more than welcome.

Here is my device for helping people to understand oil consumption in the USA:

1 million barrels = 1 hour of USA oil consumption

1 billion barrels = 1 month of USA oil consumption

1 trillion barrels = 1 human lifetime of USA oil consumption

Before I came here and clued in, when I read "18 billion barrels in coastal offshore" I thought "oh good, centuries more of supply!"

Armed with this device, I now think "oh no, 18 months more of supply!"

Thanks bmcnett,

Good stuff, I am going to print it out, stick it in my notes, and use it in talks.

Another way to understand Peak Oil:

Global crude = 862 barrels per second

Global liquids = 1000 barrels per second

When the number of crude barrels per second goes from 862 to 850 per second, something has to be cut out. Crude is 95% of transportation, the base for industry and manufacturing, and much home heating. Since there is little conservation, it could be less use of automobiles, air travel, commuting to work, higher prices, recession, job loss. When it goes to 800 barrels per second, yet less auto travel, commercial air travel collapses, and so on.

At this point, ie. 800 barrels a second, all oil will be used just to keep basic economies moving (the government wants to stimulate the economy to keep people employed and thus consuming oil), thus no demand destruction as we head toward terminal depletion. Oh that terrible word, terminal. Yes, we are a terminal case.

Also, the U.S. is using just 216 of the 862 barrels per second. If the U.S. conserves, and other nations do not, then the high demand in the other nations' 646 barrels will consume the little amount that the U.S. conserved, say 6 barrels per second. Thus the depletion rate, heading toward terminal depletion will look much the same. Oh, that word terminal again, but terminal depletion is reality.

But the U.S. is in a worse position than the rest of the world, with less oil exported and a bankrupt USA that can afford to buy oil at $1,000 a barrel. Before too long down the slope we won't be able to run the transportation system and heat homes and institutions. The highways will collapse without maintenance and snow plowing, and the electric power grid will fail. After the last power grid failure, nothing comes in from elsewhere and no communications. Sounds like a terminal case to me.

Another startling figure is the US consumption of gasoline at 388.6 million gallons/day. That's 141.839 billion gallons/year. Now ask if 1/4 of our corn crop is worth converting into 6.5 billion gallons of ethanol.

But when oil starts getting short in supply, food is also going to get short in supply. Oil at that point will not be priced and paid for in currency but in food.

The USA is one of the biggest food exporters so I am guessing that the Middle East countries that are very dependant on food imports are going to be very happy to send oil to the USA for food.

Countries like China and India are big importers of both oil and food so they may have a difficult time coming up with food to trade for oil.

Countries like Brazil that have food for export are also going to be oil exporters so they will not be in a good position to trade food for oil with the Middle East, but will be supplying what exports they have for commodities like raw industrial materials.

The straight global currency trading system that currently exists is going to see some major changes post peak oil.

When people think post peak oil they are going to have to "think outside the box" about a whole lot more things than is currently being done.

just a reminder ,keep in mind the US is importing oil in a ratio of exporting food at $6 : $1 =>> $6 out per $1 in.

(obviously the US has more dollars in from other exports)

I agree 100% in general.

But corn ethanol or other stupid food->fuel schemes can rapidly cut into this.

The US as its own version of export land with food. Food prices in the US will follow the open market prices or subsidies will cut exports etc so it does not help the average US citizen. The % of people working in agriculture is small is about 3% so being a agricultural super power does not help employment.

The moment you expand the viewpoint from one positive fact you quickly see that its not all that helpful. Will people starve in the US ? Probably not barring some sort of breakdown in food distribution. Will food be expensive and you want your own garden to minimize food expenses yes. Will we have short term food shortages because of the tight tie to transportation probably. We need to relocalize agriculture and that will take time.

But overall starving hoards probably won't be a problem in most of the US with the exception of potential problems in the North East and South West. Esp the south west which will be dealing with problems coming up from Mexico and it also has its own regional water problems since it seems to be entering into a 100 year drought condition. This is outside the scope of peak oil but important.

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/nationworld/2003645694_drought01.html

You have to perform a meta analysis about every "fact". And finally of course we have no assurance that the traditional spread between food and oil prices will not close in fact we can expect exactly this to happen as oil get more scarce we will trade it on a more equivalent basis for food. The food supply is not decreasing outside of misguided food->fuel concepts but I suspect it will quickly become obvious that the best use for excess food production is to sell it for oil instead of converting it to ethanol.

These kind of lies make us sound like gluttons. We only use a miserly 862.4 thousand barrels an hour. What kind of wasteful pigs do you think we are?

My figures check out. How do you figure, and it is not clear who you mean by we.

Did you know "sarcasm" isn't listed in the dictionary?

Actually maybe I'm the one reading him wrong. I understand your predicament reading the news. Won't bother to dig up the link but I think it was on bloomberg, some "expert" saying prices would retrace and demand would double over the next 20 years. Oy Vey.

CJwirth,

Your figures are correct. There is even a book called "A thousand Barrels a Second". It works out at about 4.5 cubic kilometres, or for those who prefer imperial, 1.1 cubic miles of oil a year. We are wasteful pigs I'm afraid!

As I've pointed up before, exportland is just one example of a generalised rule. In a supply constrained market, access to oil becomes even more fractured. For every factor certain groups maintain 'easy' access. The others face a swifter decline rate as the pain of decline falls almost directly on them.

To date we have seen the action of price, pushing certain consumers out of the market - predominately those in the developing world and non-essential poor users elsewhere. Call that "priceland" or business-as-normal.

We have also begun to see "exportland" take effect, with the few net exporters left resulting in the predicted effort on world supplies.

Other effects we can expect include:

Each factor acts as a multiplier for those affected, increasing the rate of decline and shortening the time for adjustment and until they have no hydrocarbons. A simplified, indicative graph might look like:

While 'exportland' is a key factor with a large multiplication effect; elements like 'rationland' are equally key for their effect on the common man. While 'exportland' is a game of geopolitics and multilateral action, 'rationland' is about how national approaches to declining supply are handled. These are much more within our control. Do it well and the decline can be managed. Do it badly and those disadvantaged will fight back with the inevitable risk of civil war.

I'm not understanding you graph. Would not rationing reduce base production?

Chris

Nope.

Rationing is providing preferential access to available oil imports. So if 10Mbpd is the available import level, 5Mbpd (say) are allocated for police, farming, ambulance, politicians, key workers etc.

5 years later when imports are only 7mbpd still 5mbpd are allocated for those uses - resulting in only 2mbpd for everyone else. 30% reduction in imports results in 60% reduction in available fuel for the man in the street. The average annual decline rate of 6% becomes 12% - eg its an additional multiplier for this group.

I see, you are just shifting labels on how the oil would be used in any case. Rationing which cuts overall use would, of course, cut production unless storage could handle the excess. Rationing that affects prices is a different sort of thing.

Thanks,

Chris

Not sure that really hits the point of it.

Its not about prices, its about allocation of resources and available resources once deductions have been made. 'exportland' makes an allocation of domestic exporter uses before determining available exports for sale. 'rationland' makes an allocation for national 'key users' before making the rest available to those that can get it.

Price ('priceland') is another matter that can also limit usage by groups - but my contention is that this will become less important in future as national governments take charge and international politics sets export numbers and directions.

Your graph shows well why we must implement something like the Oil Depletion Protocol.

Note to editors, rating system not working.

Yes, the graph already has producers setting production to raise the price. The question then is can consumers force the producers to produce even less through their own rationing policy. That is, not just allocate what is available after producers set their policy but trump the producer policy by refusing to consume at that rate. This would perhaps thwart the producers' intentions.

Chris

You also get this same sort of fracturing on the production side. The best light sweet crude commands a premium and drives of the prices of heavy sour reducing the spread and making them uneconomical till the spread widens etc.

Globally the market misallocates resources with crude shipped from the middle east refined in the US and then the refined products shipped back to Europe as price imbalances cause oil and finished products to take stranger and strange routes before finally being used. The point is that oil production itself becomes inefficient. Subsidies have this effect also with drawdowns in storage until you reach danger levels followed buy sudden bursts of demand with more oil bought on the spot market. This leads to producers more willing to wait for spot contracts instead of less lucrative locked in contracts.

WestTexas noted that the US is now being forced to buy oil from farther and farther away as local suppliers decline. These various new inefficientcies are large enough to have there own real effect on oil distribution greatly increasing the time between when oil is pumped and when its finally used.

Also of course as absolute imports of oil decline in refining countries exports of gasoline and diesel from oil importers that are refining exporters will decline sharply similar to what you have described. Also the US which is both a oil and finished product exporter is competing with its finished product suppliers for oil. In my opinion we will see exports of finished products from refining nations drop sharply as they refuse to export to the point that they cause domestic shortages.

Once this starts the decline in finished products available for export will be nothing short of breathtaking as large multi-importers like the US drive up finished production export prices and prices for the best grades of crude to run its own refineries at maximum. For a time at least refineries will again enjoy huge margins. If the governments attempt to control prices then shortages will rapidly develop like the 1970's.

So you see how the base export land models drives other similar export land like problems throughout the oil markets.

At some point of course production which has been driven hard begins to really decline. Also oil production itself is now a politically charged issue with Venezuela's reported production blatantly wrong but we have to expect that other oil producers are willing to decide to not report "temporary" declines or do things like double count oil that was produced but stored locally as production twice.

In any case it seems that way to many variants of export land are now in motion to really even understand the magnitude of the combined effects but it seems that overall they seem to be contributing to even lower real oil utilization.

And how can people move if they can't sell their house? Have you looked at the housing market stats lately, and it will get worse in the Peak Oil crisis, the values of homes will drop tremendously.

They will continue to do what most are doing today they will allow the house to go into foreclosure. The smarter ones will probably rack up huge credit card debt and file bankruptcy. Credit does not mean a lot if you don't plan on buying a home or a car. It was only important for a car/suburban society.

This is important to understand since or fiat/debt based monetary system is based on the willingness of people to take on huge amounts of debt for most of there productive lifetimes. Most of this debt is in homes and cars with college educations making up a large percentage of the remainder. After this credit card debt to buy stuff for the home gas for the car and meals out because your to busy working servicing debt to cook make up the remainder. The revolving or unsecured debt is needed because most of your income is spent servicing your fixed asset debt.

The fiat currencies work because it benefits the debtors devaluing there debt load over time. It benefits the lenders because it keeps defaults low on long term debt and real interest payments are far in excess of the amount lost via inflation. Not to mention they are loaning effectively free money.

Once the game is up and these assets are deflating in value and peak oil/ food prevents the Central banks from inflating since this just drives commodity inflation with no change in wages the party is over. People don't need credit they need cash to pay for food transportation and the rent. The amount they pay for rent is the one variable they can control by adjusting their living conditions to lower rent payments.

The game is up the party is over. Homes are only worth what people can pay for them in cash or with a huge down payment say 50% or more.

http://www.escapeartist.com/OREQ12/International_Real_Estate_Investing.html

As the cheap oil fiat currency party unwinds the US will have to adopt these sorts of loan down payment requirements. And rising transportation costs and rising food costs ensures that most of the population will have to spend more on daily expenses and the chances of most to ever save this level of down payment given spiraling commodity prices and dropping wages. ( Remember we are a service economy that has to transition back to a producing economy ) is so close to zero its not worth discussion.

Only the wealthy will be able to buy houses for rentals and even for them the price they are willing to pay will drop steadily as the purchasing power of people erode and they take on higher density living arrangements.

I know a lot of people me included are planning their post peak oil lifestyles but unless your filthy rich you better understand whats going to happen to housing and land values.

If you think you can buy a farm for cash that will be productive and you can afford to write off the devaluation of the property thats your decision.

If your willing to speculate on land near rail lines you may be a winner if its needed for high rise development however unless your in the in crowd in your city you probably will lose it via imminent domain tricks and a low valuation. So there is potentially money to be made buying up cheap land in the current ghettos but its a really risky proposition.

So in my opinion if you have long term debt you better sell the assets and eliminate the debt. If you own land and property and are dependent on it retaining its value then you better sell yesterday.

If you own it and don't care about its value no problem esp if it produces a income its just a paper loss and if you have to sell in the future you can always buy a equivalent property. As long as you are not leveraged in a loan selling and buying a equivalent or smaller property results in no loss of utility.

If you own a home outright now and its worth 500k and 10 years from now the same home is "worth" 100k big deal you can still sell and buy a similar house.

If you sell now and invest the money so it does not lose value you probably could buy a lot nicer place later if you wished but really this is not a big deal.

Its not all that important. If you own your home outright then you should probably have enough money in savings to upgrade later if you wish.

But the important thing to realize is that the majority of the people are going to default on their debt and a lot will lose there jobs and take low paying jobs as we have to compete with china to rebuild our manufacturing base and rail systems under conditions of high oil prices and high food prices. No one will have much money or need for long term debt. Not to mention yet again once the defaults really start going people who could take on the debt will be unwilling to because they are scared they will default later since everyones job will be iffy.

Read about the Great depression etc because we cannot inflate our way out of this. We don't own the oil.

Your argument as to why it would not be possible to inflate away the cost of housing needs expanding.

Others argue that hyperinflation is inevitable, in the case of the US and possibly the UK.

For the specific case of the US, its own oil production is substantial, enough to provide power if private cars are virtually abandoned.

With millions about to loose their homes, not the numbers current but vastly greater, enough to provide a political imperative, then the pressure will be immense to inflate away housing debt.

American food production is still going to be wanted, and barter arrangements seem likely.

The issue might also be finessed, so that a moratorium is placed on repossessions or perhaps a 'fair' limit is placed on interest rates, so that the inflation is in one way or another rather hidden.

It is perhaps rather more difficult to see the UK getting away with a direct devaluation, so that socialisation/nationalisation of the housing stock may be more likely.

In general, there are usually alternative measures available, although all of them may be unpleasant.

For that reason it seems to me ill-advised to be too deterministic about outcomes, as choices will influence them.

As an example, it seems quite within the bounds of possibility that the US will simply seize the oil it needs, and put oil fields beyond the reach of attack by disgruntled locals by killing them/imprisoning them.

Such a militaristic hothouse would look very different to a depressed community trying to re-adjust to more eco-aware living.

We have certainly entered the era of consequences now.

Couldn't this be illegal in some areas and can't you be forced to pay back the debt?

I am not too worried about college debt because what are they going to do, take away my education if I can't pay it back in a post peak oil world?

It's kind of funny we are moving back towards the olden days when you had to save up your money in order to spend it, the current economy will have to massively collapse before we get there again though because the economy could not tolerate such a high savings rate?

Big fan of your post Memmel, keep em coming

Crews

In 10 years that $500,000 home will be worth $5,000. Tens years away is a long time down the depletion curve. Much can happen in that time, and not much will be good.

What happens to an export land when its oil production is less than its consumption? If it is Britain, it has other items to export. If it is a place whose economy has always come largely from exporting oil, and it has not invested wisely through whichever mechanism it uses, some being much less likely to work than others, it has a serious problem relative to traditional oil importers that actually have an economy to shield them.

1. Pure Exportland's economies crash earlier than their exports go to zero

2. UK does not have so much other things to export anymore. Remember, becoming net importer is double pain: first they lose the export profits for oil, then they lose the money that goes to paying for imports. Please see Euan's excellent article from a few days ago: http://europe.theoildrum.com/node/4188

3. The countries that export, will hit problems with their exports once global peak is reached (or plateau is long enough): costs of exports rise rapidly and as such, eat away the profits of exports. This in turn raises prices and reduces demand for such exports.

Yes, being diversified is good, yes having some imports other than oil is good, but being fully export dependent, be that fossil fuels or other exports, isn't going to be optimal. The worst option is to be systemically food import dependent on all major food items.

Thanks for a fine article.

A recession/depression might no increase the amount of oil available, as extracting most of the remainder is dependent on very high prices.

If the world economy cracks under the strain (when it cracks, in my view) and the oil price sinks, projects become no longer viable.

Even when, or perhaps if, the world economy recovers, it would be once bitten, twice shy, and investment for very high cost oil would be difficult to come by.

Any extraction of these very high cost reserves would not occur then, at least until a complete change had been made, and the world economy was no longer so dependent on oil that it no longer had the power to cause a recession.

In that case, why bother extracting it?

So rather counter intuitively if this is right then decline rates of production will be similar, regardless of whether prices drop back due to recession or not.

Think of Brasil. If they can, why wouldn't they extract oil and gas from the sub-salt layer, to use themselves? That oil won't be traded internationally, hence high prices will have litle to do with it.

During a recession commodities prices will go down, hence problems won't arise from there. In the end it all comes down to the EROEI of those reservoirs. If it is confortably positive that oil will be extracted.

A lot of investment will indeed take place at different levels of price.

However, to take a different example, the hunt for oil reserves in the North sea will doubtless be pursued rather vigorously if oil is at $200/barrel.

If the world economy falls off the cliff so it is only going to get $80, how hard are companies going to look for this expensive oil?

Even if the oil price later recovers, knowing that it could fall again as the world economy can't sustain very high prices would mean that investment in the ultra-high cost reserves would be too risky.

EDIT:

The thought I am trying to get across is that if the world economy can't take ever higher oil prices, then the very expensive stuff gets stranded and is never produced.

For the oil exporters their revenues are also reduced compared to what they would have been if the oil price just went up and up, so we are in a situation of demand destruction pure and simple.

"In that case, why bother extracting it?"

Phew. I'm pretty glad I found something to disagree with Dave because otherwise I was beginning to think someone had copied my memories and downloaded it into a cylon copy!!!

Anyways:

the reason why oil will be extracted is quite simple: selling price - cost price = profit and the energy exists to extract it.

As long as energy is available to extract oil and the dollar price of doing so means a profit can be made, then it will be extracted.

The oil sands are a case in point: though the EROEI is very low, the price is very high, so it's worth doing in dollar terms.

The key question in my mind is more about the point when it becomes cheaper to use electricity directly from energy producing renewable infrastructure instead of using the energy produced from said infrastructure to subsidize low EROEI oil.

Will we ever get to that point? The answer is the key distinction that separates the doomers from the optimists.

The EROI is important, but if the economy is able to weather very high oil prices and both the economy and the price remain stable, or in the case of the oil price not to drop, then it is possible to sustain investment at relatively low EROI.

If the economy is in tatters, then you need a higher EROI to justify the investment, especially if the price swings, as the economy is permanently teetering on the brink of collapse which would knock oil prices lower, making your investment uneconomic.

It is a result of the instabilities expected at peak, which several people have commented on.

The oil sands are something of a special case, as they have massive reserves and we know exactly where they are, so any progress in increasing EROI is absolute and can be expected to generate money for many years.

The EROI for this source seems likely to be pushed up to very reasonable levels, in my view.

It is the flow rate which means that it will not support oil use on anything like present levels.

Figure 5 only works to a point. Lower exports will not always result income increase as suggested. There will come a time when importers can't pay higher prices or the higher prices are not enough to more than compensate for reduced volumes - resulting in lower income, and halting the internal consumption growth.

For an exporter for which oil exports are a minor part of the economy this effect is not important but for an exporter for which oil is the most significant part of the economy Figure 6 must be false, or at least only describes a temporary situation before internal consumption collapses under recession allowing a degree of export to resume.

The CIA World Factbook says Indonesia’s GDP is $432.9 billion, their oil production of ~1mbpd is only worth some $47bn at $130 a barrel, their exports over the last decade of some 300kbpd at say $40 were only worth $4.3bn per year, just 1% of an economy growing at over 6% per year. They could afford to still grow the economy without the oil exports.

Similar rough calculations for the big exporters show the value of oil exports to be a large proportion of GDP, far larger than the economic growth rate.

Saudi Arabia:

GDP = $376bn

Oil exports = 8mbpd

Value at $130 = $380bn

% of GDP = ~everything!

GDP growth rate = 4.1%

Russia

GDP = $1286bn

Oil exports = 7mbpd

Value at $130 = $332bn

% of GDP = 26%

GDP growth rate = 8.1%

UAE:

GDP = $193bn

Oil exports = 2.5mbpd

Value at $130 = $118bn

% of GDP = 61%

GDP growth rate = 7.4%

Norway

GDP = $392bn

Oil exports = 2.3mbpd

Value at $130 = $109bn

% of GDP = 30%

GDP growth rate = 3.5%

Iran:

GDP = $294bn

Oil exports = 2.3mbpd

Value at $130 = $109bn

% of GDP = 37%

GDP growth rate = 5.8%

Kuwait:

GDP = $111bn

Oil exports = 2.2mbpd

Value at $130 = $104bn

% of GDP = 94%

GDP growth rate = 4.6%

Nigeria:

GDP = $167bn

Oil exports = 2.0mbpd

Value at $130 = $95bn

% of GDP = 57%

GDP growth rate = 6.4%

These countries can’t even come close to maintaining economic growth (and with it internal consumption growth) without large oil export revenues. Their exports will not come close to zero due to internal consumption growth.

The UK and Indonesia examples are not two extremes – they are two examples of the same: large economies to which oil exports were a minor contribution. They are not typical of major exporters.

The UK exports fell an average of some 500kbpd over the last decade at an average price of some $40 they were worth only $7.3bn a year in a ~$2,500bn economy, a third of one percent!

As oil exports fall, growth rate must also fall and with it internal consumption.

The curves on Figure 6 should be curved and not even come close to meeting for today's significant exporting countries.

Chris, superb post which surely throws new light on the ELM.

Just a thought to muddy the waters a bit!

Perhaps a distinction should be made between those countries with massive sovereign wealth funds and poorer countries - so we are talking about Saudi, Kuwait and the UAE.

Although Russia has a lot of money, relative to its economy it is not so large.

In theory, and perhaps in practise due to political reasons, with the politicians not daring to tell the public that the good times are not going to roll forever, a high rate of growth could be sustained for some period of time after oil exports dropped, basically by running down their capital.

How long depends on the size of the sovereign funds.

I doubt this argument amounts to more than a quibble on your critique, save possibly in the case of Kuwait and the UAE, but if anyone has the figures it might modify expectations somewhat form that which you so ably lay out.

Of course the key factor is price. As the world net export decline accelerates I expect the cash flow from export sales to increase, even as export volumes decline. I've suggested Phase One and Phase Two declines in specific countries.

In Phase One, the cash flow from export sales increases as export volumes fall, as oil prices go up faster than volumes fall.

In Phase Two, the cash flow from export sales falls because rising oil prices can't offset the decline in volume.

Saudi Arabia, for example, is clearly in Phase One, with two years of annual net export declines--and an accelerating rate of increase in consumption.

Of course, the presence or absence of subsidies is a factor, but what these case histories showed is that once an exporting regions starts showing lower production, their fate as a net oil exporter was sealed (Indonesia had subsidies, the UK had high taxes).

Ultimately, I expect that a lot of world trade to be reduced to trade between food and energy exporters.

"Of course the key factor is price"

I must quibble a little with this.

The key factor is PROFIT.

Both in dollar terms and in energy terms.

If price drops but costs drop correspondingly (or quicker) then profit stays static or actually increases.

Costs can drop by increasing efficiency.

So my argument is that oil production will NOT be curtailed by a price drop unless costs cannot be controlled or reduced.

In any case, we have a real life ongoing example of the Export Land Model, Mexico. Like "Export Land," Mexico was consuming about half of production in 2004, and I estimate that the net exports in May, 2008 were down to about 1.1 mbpd, versus their peak annual rate of 1.9 mbpd in 2004. It will be interesting to see how it plays out from here.

BTW, another factor of course is voluntary restraints on production, as it becomes clear how finite oil resources are. In both Kuwait and Saudi Arabia for example, there have already been discussions along these lines.

Using 1.9mbpd exports in 2004, a 2004 oil price of $40 produces a annual value of $28bn. Mexico's economy was ~$800bn in 2004 (subtracting the GDP growth from 2007's GDP of ~$893bn), so this represented 3.5% against an annual growth 4.2% in 2004, 3.0% in 2005 and 4.8% in 2006. If Mexico is now down to 1.1mbpd at $130 the annual value is $52bn (5.6% of GDP). Economically they are fine, for now.

Again, like the UK and Indonesia this is a different category to most of today's major exporters.

Here's an idea of what I think Figure 6 should look like:

The key point is to carry the model out to the vicinity of zero. If we assume no increase in consumption, Export Land would go to zero net oil exports in 14 years, instead of 9 years--not exactly a big difference, and I haven't run the numbers but at a +2.5%/year rate of increase in consumption, only about 10% of post-peak production would be exported. I'm guessing that a zero rate of increase in consumption would result in about 15% of post-peak production being exported (I assumed a peak at 55% of URR, using Texas as a guide for URR, relative to peak production).

BTW, assuming a flat consumption rate of 2.1 mbpd for Mexico, their net exports were about 1.4 mbpd in October, 2007 and as I said, about 1.1 mbpd in May. At this volumetric rate of decline, they will be approaching zero by late 2010. At half this rate, they would only make it to 2013.

As I have previously noted, both the US and Europe have problems with net export declines from Proximal Petroleum Producers--Venezuela & Mexico (VenMex) for the US and Norway & Russia for Europe. In October, VenMex accounted for more than 20% of petroleum imports into the US, and from October to March, the volume of petroleum exports from VenMex to US shores fell at an annualized rate of 32%/year.

I think that this is a big contributor to the accelerating rate of increase in oil prices, as Europe and the US have to bid the price up to redirect oil cargoes away from their traditional destinations--as we try to offset the declines from the proximal producers, at the same time that China is trying to increase their imports in order to meet higher demand.

I think that if you want to take a vacation to Mexico, you should do it now. I'd guess that in another couple of years you'll need an up-armored Hummer equipped to run on biodiesel. And don't forget the 50 cal gun mount.

I greatly appreciate your constant ELM drumming. What's surprising is that it hasn't taken better hold with the media's talking heads. It is so basic yet so rarely mentioned. There was a post a few weeks back (you, perhaps?) that listed global export volumes since 2005 and ytd for 2008 which calc'd out at -1.4% a year, which just happens to be the decline rate for the US since 1970. Anyhow I wonder how accurate those numbers will prove. They really grabbed me. If accurate, they could well be a primary catalyst for the ensuing price trend.

But as bad as the situation in Mexico is, Russia is still the big question mark for me. When a producer of that volume goes south, the world is screwed. So far this year ain't looking good and the BP stats show that their R/P ratios sucks.

BTW, TruTV has a reality show called "Black Gold" that features drilling crews in west Texas working the Permian Basin. That's some nasty work.

I think you are referring to this chart:

Note that while this chart appeared in a post on declining net exports from Venezuela and Mexico that I did, the chart was prepared by "Datamunger."

Mucho Thanks,

When I was a kid I was scared of the critters in the dark. This is what scares me now:)

Chris,

That's precisely one of criticisms to the model that I referenced. If you read closely the text deals properly with it. Let's look at a particular case:

Mexico exported 1450 kb/d in 2007, which at 75 $/barrel sums up to about 40 billion $. For a present GDP just under 900 billion that's about 4.5%.

Now let's go back in to time to 2004. Then Mexico exported 1900 kb/d, which at 40 $/barrel was around 27 billion $ or about 3.3% of the 2004 GDP.

In 3 years Mexico's oil exports declined 30%, but at the same time the revenue grew almost 50%.

The only way to brake this dynamics is for a feedback to arise at the importer's side, in the form of a recession or energy substitution that retracts demand.

Another thing:

Who says so? Why will the internal consumption rate decline if exports decline? Can you give an example? Remember that population growth is a big factor in most of these countries.

I'm talking about major exporters whose economies are dominated by oil export revenue. If they lose that source of revenue their economies shrink, they can't import so many BMWs. This is not the case with UK, Indonesia, Mexico... but is the case the countries I listed above, where oil export revenue is significantly larger than GDP growth.

The question then is: how do they loose that source of revenue, if as seen above, oil prices are growing faster than depletion?

An interesting thing to know would be what fraction of GDP were oil exports in all those countries you listed, say 3, 5, 7 years ago.

"Importing BMWs" More like buying and operating scooters and small sedans for the West African oil producing countries, and buying appliances that rapidly increase electricity demand that is filled by using diesel gensets. All of this increases internal consumption.

One other thing that I think should be considered: How big a user of oil is the oil extraction industry. This could further eat into exports. This effect would increase with decreasing EROEI as you go down the decline curve.

For example, if Saudi Arabia is using more and more oil to extract their oil, this would increase consumption and reduce exports, even if the other parts of their economy were not increasing oil usage.

You are right, the ELM is based on a set of assumptions that will not be stationary in time.

Another factor is that large exporters have less incentives to increase production when prices are higher (positive demand shock), this fact is used in the EIA Short Term Oil forecast. In particular, for Saudi Arabia which welfare is completely dependent on oil revenues:

Ref: De Santis, R., Crude oil price fluctuations and Saudi Arabia’s behaviour, Energy Economics 25 (2003) 155–173.

Saudi Arabia is a ticking bomb in terms of internal consumption:

The reason is in part due to a strong demographic:

http://graphoilogy.blogspot.com/2006/02/saudi-arabias-ability-to-export-...

This seems to be subscribing to the fallacy that since oil is a 'smaller' percentage of GDP it is somehow less necessary. My guess is that as Indonesia's overall production of crude drops, its GDP will drop even faster. Over the past decades, more and more GDP has been 'leveraged' on top of a given amount of crude oil (and other fossil fuels). As the supply of fossil fuels shrinks, the leverage will work in reverse and we will get a rapid contraction of GDP in any given country.

That is, unless alternatives are able to be ramped up quickly enough to replace fossil fuels.

I'm not talking about using the oil to generate GDP, but the value of the exported oil. What happens now that they aren't exporting is anyone's guess but not not very important to this discussion.

GDP must be based on ALL oil produced, not just that exported.

Figure three - is that "future art". Frame it and put it in a gallery! maybe our grandchildern will appreciate it someday.

Hi Luis de Sousa

Thanks for the great post. You write" "As Alan Drake has pointed out, if we could do electric transportation 100 years ago in West Central Texas, with minimal oil input, why can't we do it in 2008?"

When oil is $1,000 per barrel, it will be too expensive to make big capital improvements.

The very troubling news on the collapse of the U.S. economy and dollar are an indication of how broke we are. We spent the piggy bank on big pickups, SUVs, ridiculous highway and air travel systems, suburbs, shopping centers, and lavish and ridiculously huge houses, to mention a few. Now the cupboard is bare. In the coming months that will become more apparent as the U.S. banking and monetary systems collapse.

I believe that I wrote the part about Alan Drake, in my comment.

WESTEXAS, DANBROWNE, RESEARCH24, TENTHOUSANDMILEMARGIN, AND KARLOF1,

That was yesterday, today is a different day. Yesterday we had easy coal, oil and natural gas. Not anymore. And now the scale needed to transform transportation is immense.

There will be plenty of cheap labor available soon enough. But the capital costs of electrifying the transportation system at $1,000 and $5,000 per barrel are high. The capital costs are the oil, natrural gas, and coal used in mining, manufacturing, and transporting the equipment for a whole new economy. That oil will soon be needed to just keep things going -- maintaining the interstate highways, semis moving food, snow plowing, tractors, combines, home and institutional heating, basic government services (local/state/federal), hospitals, school bus transport, schools etc. The dollar and U.S. monetary system are collapsing today. We won't be able to buy the oil to make all of the electric trains and light rail and infrastructure of hundreds of thousands of miles of power lines, stations, rails, electric power generating stations that are necessary to have an electric transportation system. Get your calculators out and begin to calculate the magnitude of infrastructure you are talking about in a nation of 300 million people who are dispersed all over the country, not just in cities. Take a look at the vast coverage of the highways we have all over this nation.

Many people on this site are great at calculating oil depletion rates and land export models. Use those skills to look at the economics of doing this from the standpoint of how much will oil cost and what will we be able to buy and what will it be used for. The trade offs will soon be: do we heat people's homes or invest in light rail? You can see what will win out. This is real now. Many people cannot afford heating bills this winter and state governments will have to pull money from other areas, such as highway maintenance, then the decisions get into emergency choices. The investments needed for a transformation to an electric economy will lose out over keeping people alive.

Cheers,

Cliff Wirth

100% correct. The summer driving season is discretionary for the most part. But the fall harvest and winter heating is not.

However we do have a way out and I'm sure we will use it.

My argument that electric rail won't save us is that even if we do it most of our housing stock is poorly positioned and our cities poorly designed to take advantage of rail. This means that we will still suffer a major deflation in house and land prices as cities contract around rail lines and become walkable. The is Kuntzlers end of suburbia. On the other hand by massively depreciating our housing stock and not paying outrageous sums for rent either directly or in the form of renting money for a mortgage and of course stopping the building program and endless sprawl we free up a enormous amount of real capitol that previously went into homes cars and roads. Also of course as we refuse our are unable to pay much for homes everyone gets a steep discount in the cost of living allowing us to also absorb higher gasoline prices.

Right now the density of people per living unit in the US is about 2.6 if this rose to 3.6 as people reduced housing costs to cover other costs we would have like 35 million extra living units. This is certain to crash property values.

Of course areas close to public transport will probably fare well and increase in value so a lot of our now poverty stricken inner city regions will probably get a windfall this steep differential will help drive investment in public transport and electric rail since the only way to make money in real estate would be associated with good rail transport.

So once this dynamic starts happening we will get our public transport. Given that most of the middle class has deeply invested in homes and even most of the wealthy in real estate a enormous amount of notational wealth mostly debt will be written off. The neat thing is most of the housing stock thats free of loans is also the older stock located closer to the city center so even though we will see a overall decline the people that paid off there homes and stayed in the deteriorating neighborhoods may well come out better than most.

The amount of debt that will be defaulted on and the nominal drop in the value of most of the housing stock is huge certainly enough to wipe out the middle class and probably destroy our current financial system but its notational wealth and real assets that are being depreciated its not the end of our daily economy.

What happens as the value of the housing stock and cars etc are written down and people move close to public transport is that as there notational wealth goes to zero and the default on all there debt their cost of living is also dropping dramatically they are walking to work and living say 2-3 to a bedroom so even as there wages and standard of living are in a sense dropping they are still quite able to get food etc and live a ok life as long as they can get work.

Certainly a lot of the population will fall through the cracks so to speak during this transition since even as wages go lower we would still have to bring back production of basic necessities locally so the workers can work to buy them.

They no longer have credit so we go all the way back to people making the goods they need to live ( what a amazing situation ). The price of the goods would match the nominal wage since everyone would have to again really make a living.

I can't imagine why people would need to live 2 or 3 to a bedroom. Insulating houses, or at least rooms in houses, is relatively easy and cheap, heating them after insulation would only take a draw of 2-300watts and you can always ride a bike into work if you are not absolutely central.

Since new house construction would be around zero labour and wood would be in good supply, and all sorts of things can be made into insulation.

Some increase in density is to be expected, especially near the centres, with people taking in lodgers etc but I can't see a good reason why it should be as crowded as you indicate.

Sorry just to be clear we can easily crowd if you will that much if needed.

I'm not saying we have to or will but that we can. Even with less crowding its clear that people can and will move to lower housing costs to ensure they can cover daily costs. Nothing can prevent this from happening. Whatever they have to do to stay alive they will do and reducing housing costs is the primary way to achieve this.

Associated with this would also be reduced transportation and food costs. Single people living together can make cheaper buck food purchases etc. Obviously better use of the land near public transportation via new higher density structures would lower the density in a single structure.

Given that this migration if you will would leave a number of empty structures further from the rail line for those willing and able to bike walk or can afford a PV the price of these structures would be low enough to cover the additional transportation costs.

But you can see how the value of the structures drop quickly as you get away from the public transport. Your not going to pay a lot of money for a house and a lot of money for transportation to work in a low paying job.

Two things happen real wages fall and food/transportation take up more of your income the place that you can cut to balance your budget is housing costs. If this means living 3-4 to a bedroom to balance your budget you do it.

If people do do this then we would have a large number of empty building a lot more then the 35 million I mentions since that was per structure not per bedroom.

This would lower the cost of housing allowing less crowding.

The net result is housing will get dirt cheap either via crowding into a expensive but convient location that minimizes transportation cost or devaluation of the houses that have high transportation costs.

Access to public transport esp rail would be the only way to keep the value up thus a huge demand for rail.

What I'm trying to say is that the underlying reason we can and will build rail is that devaluation of the housing stock that not convenient will force the issue.

The fact that we have overbuilt and for the most part incorrectly our housing stock insures that housing costs both rent and mortgages will and can decrease as food and transportation take up more of peoples budgets. Given that most houses would be declining in value every year its not clear that mortgages like we are used to would be available. This of course leaves conversion of a lot of our housing stock to rentals but given that rents would have to be low away from public transport landlords would quickly be unwilling to pay much for homes unless they where also involved in positioning the rail road lines.

This is really just a repeat of what happened when rail was originally developed.

Towns that where bypassed quickly became ghost towns.

One sad story of many.

http://www.texasescapes.com/TOWNS/EvergreenTexas/evergreentx.htm

History is about to repeat itself.

Unless you live within walking distance of a existing rail station or otherwise are convinced that your home will not be bypassed your a fool to take out a mortgage now.

Given the above I've never been happier to be a renter.

Old Alan is not coming quite clean on whats going to happen :)

I suggest you read about the effects of the first time rail was deployed and seriously consider your housing choices.

I can bet that Alan has made a very smart choice and probably will do well in the future. I'm not saying he will make a lot a of money but I suspect he won't lose a lot like will happen to a lot of people that don't understand how a move back to rail will effect our housing prices. EV's will certainly lessen the impact this time around but we still will have a large bypass effect. And no way we can prevent the overall increase in ability to pay for housing regardless of its location.

Hey Dave, as Peak Oil impacts the economy, labor will be in great supply and it will be plenty cheap, but houses are made of wood, steel, copper, ceramics, Formica, tar paper, shingles, insulation, concrete, cinder block, brick, sinks, tubs, showers, glass, wiring, fixtures. Most of this stuff is made from oil, or manufactured using oil, and all of it is transported by oil. Building materials rise with the cost of oil, in the past, and in the future.

Well, housing using these materials or similar existed and was manufactured before the rise of cheap oil. New York City during the 19th century certainly wasn't a city of wooden shacks and shanteys.

Labor and land costs will drop. And overall your correct building a new house will be expensive but who is going to be doing that ? Existing homes can be recycled for materials to repair other homes or make additions. Soviet style cheap concrete flats can be used to create probably subsidized high density housing.

Dumps can be mined for materials that can be used for houses. Houses used to be built out of local materials they will be again. You don't need all the junk you mentioned and the parts you would like would readily be available from abandoned homes and even cities that where not sustainable.

Southern California will in my opinion be abandoned and it will have decades of not centuries of recyclable building materials. This stuff need not be moved fast and sail or empty rail cars or even horse and mule drawn wagons can be used to transport it.

I figure we don't have to build another new house for about 30 years. And the ones we do build can use recycled materials for a long time.

People selling materials for new homes will have to figure out how to make them cheaper or better or simply stop.

We built far better buildings in the past without oil and we can certainly do it again. Will the be expensive and rare ?

Probably.

But understand that every single producer will be facing this issue not just homes but everything. Even simple items such as say a glass and cup manufacture.

The cost of manufacture will be high the market for new stuff will be small plenty of glasses exist in the world esp in land fills to recycle unbroken ones and melt and reuse broken ones etc. I'd say we don't need another new glass manufactured from raw sand for at least 500 years. So expensive new glasses made with expensive oil and expensive transportation are not needed.

However glasses break and I suspect that a enterprising person will figure out fairly quickly that he can make hand blown glass at a cheaper price using a solar or wood/wood gas fired kiln. Or we use more clay/earthenware. Or more plastic cups made from recycled plastics.

So I think you can see I don't think it matters if costs rise for the current way we produce building materials we will either substitute or do without.

I'm not saying we are going to go off and live like the Amish. We can and will revert back to older ways to solve problems where it makes sense.

1.) Housing local materials/ recycle and build to last for centuries.

2.) Transportation sailing ships, solar zepplins, horses, trains. Planes for the rare fast trip. Goods won't move fast more will be stored etc. Perishable foods will disappear except for what can be grown in green houses.

3.) Probably we will keep some version of our internet. High bandwidth wireless communications and fiber optics still make sense. All this can be solar powered. And a PV unit to power a low powered computer is possible.

4.) Probably keep a lot of our medical care but anything beyond the basics reserved for the rich. The majority of people can use our understanding of how to live a healthy life to stay healthy assuming we excersize more we don't need a tenth of what we currently spend to live reasonable long healthy lives. Overall better living and eating habits will result in a much healthier population even though deaths from preventable problems and diseases may rise.

Sorry for the long diatribe again but its important to think about the overall picture a bit its wrong to look at the way we do things now and assume because they will obviously be expensive in the future that the value of certain things must remain. Look at my above list very little that we have developed in the last 70 years is really important as we transition off a oil based society.

Basically medicine, computers/telecommunications, solar cells and some airplanes.

Zepplins and trains predate the oil age. I've drawn up this list up few times and its not changed much. I'm also pretty sure what actually does become important to people in the future will surprise us.

However the McMansion and SUV are almost certainly not on the list and this includes McMansion construction materials.

memmel...as usual...I am impressed with the size of your brain and the breadth of topics on which you speak. Your diatribes are always excellent reading. Don't ever apologize for their length. I'm currently reading a couple books about Buckminster Fuller and your discussions remind me of of his thought processes. You may very well be an important "trim tab" for the future course of Spaceship Earth.

Thanks for sharing with us all and making us all better for it.

The main cost of building is labour, and that is going to be cheap.

With no new build plenty of timber etc will also be available.

Umpteen empty houses will also be 'mined' for materials.

If you wish to make the argument that 'most of this stuff is made from oil' you really have to be specific about the items - it is rather difficult to analyse.

Where power inputs are critical for production, it may more nearly be true that the are 'made from coal'

Oil will be an input, but it is going to vary in importance from product to product, so the argument needs to be a lot tighter to carry weight.

A lot of the expense of building is due to aesthetic considerations, all the granite worktops etc.

Where that is de-emphasised you would be surprised what can be done.

Standards will be a lot lower, but conversions will still take place.