Local Rail - An Overview

Posted by Jerome a Paris on July 6, 2007 - 10:15am in The Oil Drum: Europe

BruceMcF introduced us to various local transport modes as potential 'recruiters' for high-speed rail. Pursuing most of these is worth on its own, for local traffic. This diary expands on one of these: local rail. As the Recruiters diary indicated, local rail is just one alternative, but it should be the backbone of any decent public transport system.

|

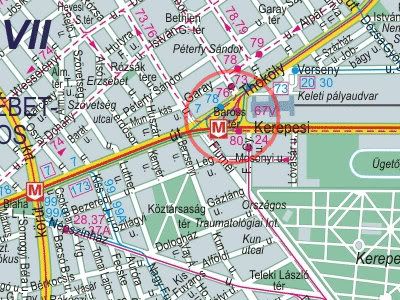

| Public transport near Budapest's Keleti pályaudvar (East Terminal): express and local rail (black), subway (thick red), light rail (thinner red), trolley bus (dashed red), bus (blue) all linked up. Blaha L. t. to the West is again a hub. |

Below, I first want to chart distinct categories of local rail: describe their specialities, their differing best uses, and some newer developments. In the real world, however, the boundaries of those categories are rather blurred, what's more, different locales use a bewildering array of rail terminology. But there are also some ingenious ideas mixing the 'basic categories', some of them will be described below, too.

This diary can also be viewed as a general guide as to what kind of projects local initiatives could aim for, and tries to give examples around the world that can be used as model for supporters and argument against opponents.

Stopping train/local service

A 'normal' railway line runs between two transport hubs (or radiates from one), and has stations in wayside towns. Running passenger transport on such a line is aimed for the outer commuter belt, it is the longest-distance (and potentially fastest) form of commuter service. It is typically also the most 'concentrated': it functions best if stations are transport hubs themselves (for buses etc.), it doesn't run too frequently, but can have high capacity.

In North America, an example could be the services around New York City still maintained by Metro-North.

'Normal' stopping trains often share tracks with freight trains. This can be both a blessing and a curse: a blessing if with passenger alone the line would make too high losses, a curse if passenger has no priority and has to face delays.

It is generally a good idea to strive for lines that don't end out in the nowhere, but in another major hub. This increases utility for passengers dramatically, and even if most passengers would almost always go to one of the hubs, the possibility of occasional trips into much more directions could draw new passengers overall: people who keep to cars for those occasional trips.

Systems centred on a city usually branch out. An old idea to rationalise such service is running 'wing-trains': two trains run together until the junction station, and then continue separately. However, such attempts were often abandoned due to technical difficulties causing delays and extra costs. But lately, this idea finds increased application in Europe, with the spread of modern multiple units in place of locomotive-pulled trains: state-of-the-art electronics and automatic couplers make the option more viable.

|

| Värmlandstrafik's X53-2 No. 3286, a wide-body electric multiple unit from Bombardier's Regina family, stops as local service in Arvika, May 2004. Photo by Jan Lindahl from SJK |

Both prior paragraphs imply a need for a good timeplan, and traffic control able to keep trains on-time. In Switzerland, the latter aim led to a reversal of the normal order of things: instead of setting up a timeplan according to the characteristics of the line, some line upgrades are built where they help the timeplan best. That is, for example along the single-track line from the capital Berne to Langnau, a couple of double-track sections (e.g. over-long passing loops) have been built, so that a small delay of one train won't cascade to the trains in opposite direction.

A novelty that sounds simple but was difficult to implement, yet brought so positive results in passenger numbers that it now spreads around the world, is the regular interval timeplan (or sometimes named by the German word Taktfahrplan): the idea to run trains at the same minute each hour (or two hours or half an hour). On one hand, this way passengers can remember times easily, on the other hand, introducing such a timeplan usually means a higher frequency, which again has a higher utility for passengers (e.g., even if some midday or late night trains run less profitably, new passengers drawn make the other trains even better earners).

On the rolling stock front, beyond multiple units, bi-level or double-deck trains also live a renaissance, also in North America. The lower floor of bi-level cars is also ideal for what has now became standard on European local trains: bike transport.

Modern railbuses gave new life to many European non-electrified branchlines. These are one- or two-car trains with compact engine packs, easier-to-board low floors, and a lighter chassis, in cases demanding special rules of traffic alongside/in normal trains. These kinds of trains don't spread fast in the USA, because AAR doesn't want to create a special category for them. Thus, either something similar but heavy (and expensive) has to be built (see Colorado Railcar's Aero DMU), or imported European trains are run as "light rail". An example is New Jersey Transit's River LINE, running GTW 2/6 railbuses of Swiss maker Stadler on a track also used by Conrail by night.

Though ridership grew healthily, constantly (from 4,200/weekday in spring 2004 to 7,350/weekday in 2006) and beyond projections(5,900/weekday), economically, the River LINE is also a truly bad example of re-starting service on an existing line. I just can't explain what cost $1.1 billion on a mere upgrade of an existing single-track 34-mile line without any major superstructures. But, since opponents of public rail transport projects like to cite it as example, I give an example of how restarting passenger service is done right.

The Schönbuchbahn was a 17 km (11 mi) branchline near Stuttgart, Germany. With no maintenance and a busy main road built in parallel, daily ridership dropped to one or two hundred, so the national railways ended passenger service in 1966. Local initiatives kept demanding a re-start, but the national railways projected only 1,250 trips daily even with full renovation, which is too little.

Then the locals pursued the takeover of the line by a regional railway, which projected twice as many daily rides: 2,500. Ambitious, given that buses carried 2,000/weekday in a region of 24,000 inhabitants. But the concept they hatched was ambitious, too:

- full renovation of the since disused track

- stations should be built where passengers can be expected

- new railbuses must be bought & locally maintained

- 30-minute regular interval timeplan

- bus companies should re-arrange their services from parallel to feeder routes

- adjustment between the timeplans of this railway, the Stuttgart rapid transit it feeds into at one end, and buses that feed it

- businesses and public institutions should adjust their work hours for the railway, above all schools

- local communities should raise a reserve pool of €0.6 mio/year for operating costs

|

| Schönbuchbahn before and after: track at kilometre point 7.4 in October 1994 (above) and August 1996 (below). Photos by Aschpalt from PROBAHN |

|

After spending €14.6 million on construction and purchase, the line opened in December 1996. On the very first workday, 3740 were carried. By spring 2003, 6,800/weekday was achieved, over two thirds left their cars, and bus ridership doubled, too. About the same sum as the original investment was spent on enhancements for the unexpected traffic load.

Rapid transit/commuter rail/S-Bahn

The dense inner parts of a city's commuter belt can bring very heavy traffic, say 10-50,000 trips a day. To manage it, railways often added extra tracks, built more frequent stops, built elevated platforms to ease and accelerate boarding, and purchased rolling stock with high acceleration and many doors. Such service could even spin off as a separate network. Thus rapid transit formed, already in the steam era.

A North American example could be the Long Island Railroad.

Recognition as separate category was the clearest in late 19th century Germany, where it was called Stadtschnellbahn ( = city fast rail). Today the short form S-Bahn is a household name. By the 21st century, all major German, Swiss and Austrian cities got S-Bahn networks as the backbone of their transport system, with other networks from subways down to buses tightly integrated at stations. Most S-Bahns use electric multiple units (EMUs) with high acceleration or locomotive-pulled double-deck trains. As opposed to normal local service, the ideal is not connecting two hubs, but connecting two commuter lines: e.g., trains crossing the city, so less passengers have to transfer. Often, multiple lines share the same central section in the city, which functions as an artery.

These S-Bahn networks carry the bulk of local rail passengers, and demand sustains a high level of further investments even if elected leaders aren't progressives, a level comparable to that spent on high-speed rail.

As an example, the Swiss canton and city of Zürich (the former has 1.27 million, the latter 370,000 inhabitants) voted in a referendum to build an S-Bahn network instead of further road construction. The plan included some new lines (mainly in tunnel under the city), new tracks and stations along existing lines, and 115 new purpose-built four-car double-deck EMUs, which should enable a timeplan that on some relations is faster than for express trains. The system started in 1990, and evolved into a monster since.

Currently, 26 lines along 380 line-kilometres serve 171 stations, carrying more than 320,000 daily passengers. Traffic growth called for several enhancements. A few years ago, a two-track line was 'doubled' by adding another two tracks for express trains in a 10-km tunnel. 120 new-generation double-deck EMUs are in delivery, while the old ones remain in service. The $1.2 billion project of adding a second central artery in a 6 km tunnel is underway. (Compare to the incredible $8.7 billion cost estimate for the 3 mile long North-South Rail Link tunnel for Boston.)

|

| One of Zürich S-Bahn's second-generation bi-level EMUs on a test run: RABe 514 004 on the Winterthur-Etzwilen line, March 22nd, 2006. Photo by Reinhard Reiss, from RailFanEurope.net |

A rapid transit system doesn't need to be bound to a single large city. Near the source of the Danube, lines connecting half a dozen major towns form a circle. This circumstance inspired the Ringzug concept: the integration of all local services into an S-Bahn-type service, with lines 'bending around' the ring in horseshoe shape, platforms rebuilt, new stops and some extra track. A not yet complete ring is in service since 2003, and brought significant growth. For US conditions, I note that this system uses diesel railcars.

Heavy metro/subway/elevated

For traffic corridors within a major city, for acceptable speeds (and curve radii), you have to leave street level. There are two ways to go: up and down.

At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, both were tried. But elevated railways, while somewhat cheaper to build, still take away building space, emit noise all around, and are exposed to weather. So, while New York's system has a lot of elevated sections, the even more subway sections gave it its name, and Chicago's 'L' is rather unique in still being dominated by elevated sections. Of the few modern examples, I note Vancouver's SkyTrain, and the first lines of Taipei's system in Taiwan and Bangkok's in Thailand.

Urban rail in major cities (say half a million or more) also means corridors with the heaviest traffic (say upwards from 100,000 trips a day). You need something even more high-capacity than a normal rapid transit. Two possibilities remained for that: running trains more frequently, and providing more space to standing passengers. The first demands dedicated lines, both demand purpose-built trains. The dedicated lines can, however, extend out from the densest part, and run on the surface, much like a normal rapid transit service. New York, San Francisco has such lines, and Washington D.C.'s was built so very purposefully.

In North America, heavy-load urban rail service is commonly not even separated from 'rapid transit'. Elsewhere however, using the name of the fifth subway system in the world, Paris's, 'metro' is the generic name, and is considered a separate category, especially as many cities have both systems overlaid.

| Impressions from the busiest and most beautiful subway in the world: Moscow's Metro, with its rich 'Stalin-baroque' interieur. By Andron3 |

I stressed the importance of connection with other modes of public transport at stations. This doesn't just mean location. It's already good to have with normal rapid transit, but essential for metros to have common ticketing with buses and light rail, so that travellers don't have to buy a separate ticket or monthly card for each leg of their journey/commute. In an American context, also worth to point out: such tickets take away the stigma of a bus ride ("I'm just hopping on to the train station" will be the initial excuse).

France is also the origin of a new development: VAL type metros. The steel-on-steel roll of classic railways has the problem of low adhesion relative to rubber-tyres-on-pretty-much-everything-else. On the other hand, rubber tyres on rail don't bear too high loads, and there is the issue of interoperability with existing lines. These problems matter least for metros, with their dedicated passenger-only lines, especially in cities still only about to build their first line.

Metro systems are still growing all around the world. I give some examples of recent fast growth.

The subway system of South Korean capital Seoul started only in 1971, the system was more than doubled in the nineties, and this year it will grow to the world's third longest (after London & NYC) with around 320 km (200 mi) line length.

The Chinese boom didn't just brought an explosion of cars. A dozen major cities, above all Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, construct subway systems at breakneck speed for about a decade now. All but one are totally new, yet the aim for the three mentioned is systems the size of New York's or Seoul's in another decade.

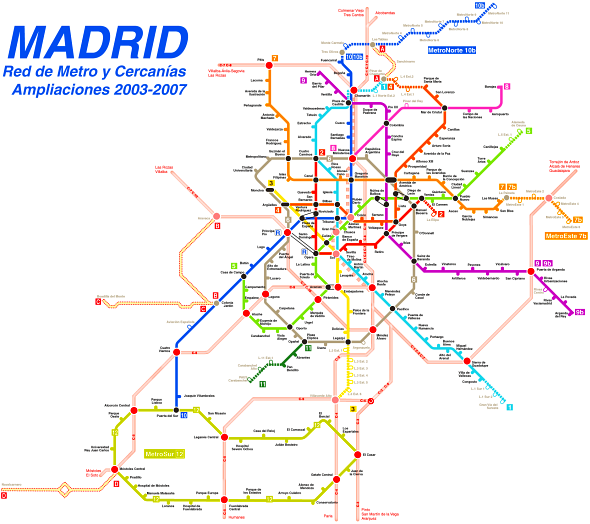

In Europe, Spain was most wise in using EU Structural Funds, and that with support from both political sides. Only Madrid and Barcelona had subways before the Civil War, not much happened under Franco's dictatorship. But today, half a dozen cities are busy boring tunnels, and Madrid's system quadrupled. For a developed Western country, Madrid should be the example to follow in how to build subways.

|

| Urban rail system of Madrid (click for full-size version). Pink is Cercanías (suburban rapid transit), red-bordered yellow is in-construction light rail, the rest subway. Dashed: built in the 2003-7 period (note that the rapid transit central artery is doubled, too -- includes a 7.5 km tunnel). Map from The Subway Page |

Metro Madrid added more than 40 km (25 mi) in a four-year period to 2003, and another 56 km (35 mi) heavy metro this year -- to a total of 283 km (176 mi) -- note that Madrid is a city of just 3.2 million. The showcase project of the previous four years was Line 12 (yellowish green on the map), nicknamed MetroSur. This ring line doesn't circle the city, but serves a couple of suburban towns by distributing traffic from radial subway and rapid transit lines. Planning, tendering, boring, fitting out with concrete lining and tracks and electronics of this 40.5 km all-tunnel line; station construction; and purchase, testing and commissioning of subway trains was all done within four years and on a budget of only €1.1 billion! On time and budget in the extreme! Compare that to the time and cost earmarked for New York's 8.5-mile Second Avenue Subway project.

Light rail/Tram/Trolley/Streetcar

In a city, one may also opt for street-level transport, gaining easier access at the price of lower speed: you have to wait at cross-streets. This idea was first tried in the USA: in New York in 1832. But it really took off in the last two decades of the 19th century, after Werner von Siemens invented electric trains: lack of air pollution and good acceleration were the decisive factors.

The new transport mode, variously called tram, streetcar, and trolley. had some specialities forced on it by streets: rolling gear and body made so that tight curves can be negotiated, cars are narrow, entrances are for practically rail-level boarding, not too high speeds allow catenary on the cheap, and special rails are sunk in the pavements. Also, with no need to be strong enough for long trains, cars could be built lighter, hence the modern name light rail.

Trams evolved for half a century (which I documented with examples from my hometown Budapest/Hungary), but then got stuck. In the USA, the PCC made the revolutionary switch from single axle rolling gear to bogies (which give a smoother ride) in the thirties, but still from the next decade, nothing held up the clearcutting of streetcar lines to make way for buses and cars. Funnily, starting from a PCC license, Czech maker ČKD became the world's biggest tram supplier during the time of the more public transport friendly East Bloc, Tatra tram parts were then even used in New Orleans. Western Europe got as far as articulated trams in the fifties, but then the big cull started there, too, and the surviving systems seemed struck in that age.

|

| All-weather service: a type T5C5K at Moszkva tér in Budapest, a Tatra built in the eighties. February 13th, 2004. Photo by Ákos Varga from from RailFanEurope.net |

That there is now an on-going light rail revival had reasons in technology. The following appeared in trams from the seventies, many of which later found their way into normal trains:

- AC motors: beyond being lighter and stronger than DC motors, they provide continuous acceleration (thus no jerks due to switching between speeds), and by using the as generators, they can function as brakes;

- disc brakes;

- rubber and air springs, dampers: smooth ride instead of the classic rumbling;

- air conditioning;

- new automated door mechanisms: you can make entrances that can adapt to platforms of different height.

The light rail revival really took off in the nineties, thanks to another innovation spurt in France:

- size reduction made low-floor trams possible, with most of the electric equipment on the roof;

- lightweight alloys could be used for lighter carbodies (though some manufacturers had big problems with these);

- departing from bland industrial designs, trams with more stylish and aerodynamic fronts made trams hip (for example Straßbourg's Tram from 1994).

Light rail is the right choice for ten to hundred thousand daily trips, not higher (or lower). With that, it could serve as the backbone of public transport in cities between 100,000 and 3-500,000 inhabitants. Above that, it's best used as feeder/distributor for heavier rail systems. For example, should the METRORail in multi-million city Houston expand into a real city-wide system and induce a large proportion of inhabitants to switch to public transport, I'm certain the addition of a proper subway or express railway would become unavoidable.

In major cities, light rail can be especially useful as further-from-the-centre orbital service: traffic volume is usually much less than on radial lines, but most people would need to travel that way at least sometimes. London, Paris, Madrid have/are building such lines. One has been proposed for the US capital too, the Purple Line, to alleviate the one big problem of the fine DC Metro.

I close this with another technology innovation from France: light rail without catenary (overhead wire). Bordeaux's new light rail line has a segmented third rail in the middle, whose segments are put on voltage with a radio signal only when a tram is above. Attempts at ground-level power supply have a 120-year history, but after heavy teething problems, this one seems to work.

|

| High-tech, style, low-floor comfort in one: a Bordeaux tram (an Alstom type Citadis302) on a catenary-free section at Quai Richelieu, August 16th, 2004. Photo by P.Chapar from RailFanEurope.net |

Light metro/Stadtbahn

Adding tunnel sections, grade-separated inner-city and perhaps out-of-city high-platform stations, light rail gains the characteristics of metros and suburban rapid transit. This is often referred to as 'light metro'. A good North American example is what became of most of San Francisco's streetcars in 1978: the Muni Metro.

As often is the case, the idea is not new, only its application as a concept. The pioneer may be the streetcar line banished into a tunnel 110 years ago in Boston, which became the core of the Green Line [so-called altough it's not a single line].

An impetus for light metro development was the reconstruction and development of bombed-out West German cities after WWII, when people saw an opportunity for reinvention rather than just reinstalment, and that relatively cheaply. Also the well-developed S-Bahn systems reduced the need for the high capacity and rapidity of heavy metro. From the sixties, a dozen medium-sized cities converted some classic tram routes into light metro networks, for example Frankfurt (see a very good map of its overlaid S-Bahn and (light) metro [U-Bahn] systems at JohoMaps). Systems with little or no subway got yet another new name, Stadtbahn.

With light metro, I shall again emphasize that notwithstanding some policymakers' claims, it is no substitute for heavy metro. The same capacity limits apply as for normal light rail.

The Karlsruhe Model (tram-train)

|

| Meeting in the freshly renovated Forbach-Gausbach station on May 18th, 2002: left a push-pull stopping train in limited-stops service, right dual-system tram No. 824 of Karlsruhe's Stadtbahn. Photo by Der Eisenbahnfotograf |

This isn't an entirely new idea either. There used to be a category of railways that ran tram-like vehicles, but on lines that go out in the countryside and then enter other towns: the overland tramway or interurban (see for example the Electroliner). Most were torn up, or converted into normal local rail, or normal light rail (if sprawl ate up the area).

Karlsruhe is a city of 286,000 in Southwestern Germany. While the city had urban trams, one private narrow-gauge overland tram led to a nearby town. Then in 1957, it came that the city got control of the overland tram. They decided to re-gauge and connect it to the system of the city proper. This took nine years, but then proved a success, and another nine years later, an expansion into a Stadtbahn network began, also absorbing former normal rail lines.

Once they wanted to get an electrified line. Then they got a bright idea: instead of buying and converting it, why not just build a connection, and buy two-system trams? Sounds simple, but a lot of technical and regulatory stumbling bocks had to be cleared, from collision prevention to train controls. But, in 1992, traffic started.

Thus the Karlsruhe model was born: trams leaving cities on normal rail lines, and leaving normal rail lines in cities. Yes, plural: once you have a bi-modal tram, nothing stops you from building tramway branches for downtown access in smaller cities of the agglomeration!

By today, Karlsruhe's Stadtbahn expanded into a 423 km (263 mi) network spawning as far as 80 km (50 mi) away from the core city, with tramway sections in half a dozen other towns, while traffic grew heavily (1960: 6 million, 1990: 19 million, 2005: 63 million rides).

So far the model was copied in a number of other German cities and in the Netherlands. Two East German cities applied the idea in reverse: in Zwickau and Chemnitz, the railbuses of normal rail lines enter town on tramway tracks.

|

| Rail bus VT 42 of regional railway Vogtlandbahn next to a normal tram at Zwickau Zentrum on February 10, 2002. The tram is narrow-gauge, so joint sections are 3-rail, but stations are separate. Photo by Marco van Uden from RailFanEurope.net |

RER

Réseau Express Régional (=Regional Express Network) is essentially nothing but rapid transit resp. S-Bahn in another language, French. Indeed one system called so, that of the Belgian (and EU) capital Brussels, is indistinguishable. (As I mentioned above the fold, local rail terminology is totally chaotic.)

But the reason for a separate treatment based on the first RER, that of Paris, has to do with long city tunnels.

This again is not entirely new. There is the through line formed by the tunnels into New York's Penn Station (1910). There is the North-South central artery of Berlin's S-Bahn, which has six stations along a 5.9 km (3.7 mi) tunnel (1936/1939). The latter is an example of cities with (multiple) terminal stations pursuing underground connection of commuter lines. Younger examples are the rapid transit central arteries of Madrid, Frankfurt, Munich, Zurich; and Seoul's metro line 1 is co-used by suburban trains.

In Paris, the connection of the suburban lines going into the eight (now six) terminals was pursued from 1969 as a network concept. While suburbanites 'see' commuter rails bundled together into five rapid transit line families, for city-dwellers, the inner sections function as an express subway: today RER trains traverse four long tunnels (altogether 60 km/ mi underground). The in-the-city part of RER line A is the busiest non-Japanese heavy rail in the world (273 million trips a year).

|

| Extreme capacity: lots of wide doors and two levels of an SNCF MI2N (series Z 22500) EMU at Haussmann-St-Lazare station, on the underground part of line E, January 1st, 2000. On line A, two five-car units form a train. Photo by Jörg Kuntz from RailFanEurope.net |

What I described is something for the largest cities. Similar systems are planned in London (Crossrail) and Shanghai.

Conclusion

I emphasize again that the presented good examples from around the world are meant for use as argument of how well things could be done, and named bad examples from the US to stress that it doesn't have to be that bad. Of course, all is not well elsewhere too, there are plenty of projects over budget due to corruption and/or incompetence, and existing systems not in the best shape.

| Subtitled trailer of genre-mixing movie Kontroll, whose anti-heroes are loser ticket controllers on a nameless ex-East-Bloc subway (filmed in its entirety on lines 2, 3 of the Budapest subway). |

But the good news is that today, if you achieve a halfway decent ridership gain on an urban rail project, even on a scandal-ridden one, you gain a supportive subpopulation. People who may complain and growl, but will put enough pressure on local leaders to maintain the line, what's more, will demand extensions.

One thing is sure: even without overpriced projects, fitting all the car-dependent US cities with local rail systems would cost a helluva' lot of money. But so what. If you get the ball rolling, you can get the critical mass to support it. As the Zürich example shows, people may even vote in a referendum for rather expensive projects calling for their tax money.

Don't go for flashy futuristic projects, or follow those claiming a super-cheap alternative. Look at what best suits local conditions, focus above all on potential ridership.

Always think in networks, even if a line built will be part of one only in decades. And coordination with other modes of transport, or even work hour schedules, is essential. This involves road traffic: say, you need new traffic lights and information campaigns for car drivers who lack life experience that a even a streetcar can't brake for them, but is so much stronger it can crush your signal-ignoring car -- to avoid frequent incidents like on Houston's METRORail. But just in public transport, you can have several levels, all for differing kinds of travel, superimposed and linked up, say these seven levels:

- high-speed rail (to get to major cities up to 800 km/500 miles away under three hours),

- express rail (to get fast to smaller cities in a few hundred km/miles, or from those to the next two major cities),

- normal stopping trains (to get to towns and exurbs around a major city, or from those to the next two cities),

- rapid transit (for rapid commute in the dense inner parts),

- metro (for travel in the city unhindered by street traffic),

- light rail (for travel on major streets to get to your neighbourhood/near your workplace/shop),

- buses (for travel within a neighbourhood to within a minute or two of your destination).

Streetcars 100 Years Ago

http://www.familyoldphotos.com/tx/2c/chadbourne_street_trolley_san_an.htm

I frequently post this picture because it shows, as Alan Drake has pointed out, that we had local electric transportation (in a small West Central Texas town of of about 18,000 people) long before we had widespread use of cars.

IMO, we need to be ready to suggest "FEOT" plans as food and energy prices continue to escalate. FEOT = Farming + Electrification Of Transportation (EOT), ideally combined with a crash wind + nuclear power program. Even on a local basis in small towns in agricultural areas, we will need ways to move people and produce around, without the heavy use of fossil fuels.

I don't know if we can make a difference, but at least we can try, and we need to be thinking hard about what to do with hordes of angry unemployed males, especially here in the US, as we transition from a highly energy intensive economy focused on meeting wants to a much less energy intensive economy focused on meeting needs.

Regarding oil supplies, I think that it is later than most of us think, and IMO, from the point of view of oil importers we are looking at a crash in net oil export capacity.

Jeffrey

I have a good friend who is involved in Railway planning here in Australia and he says to me, " we need to get the shift of investment from road to rail very soon due to the time taken to get these rail projects done."

On a recent trip to Canberra by train, I thought long and hard about Kunstler's speech to the Commonwealth Club as the train passed old stations in a varied state of disrepair and gulped at the massive effort that will be needed to rebuild the rail system. Especially where they were used to ship bulk goods.

After tearing up branch lines and closing rail lines we will see the stupidity of letting economists rule the decisionmaking process. We have a lot to do.

The following story regarding electric light rail in North Texas was repeated countless times across the US, when marvelous light rail systems were abandoned, because of the automobile. But as Alan Drake has pointed out, if we did it 100 years ago, we can do it again.

http://www.plano.gov/Departments/ParksandRecreation/Parks_Facilities/int...

There was an excellent Interurban linking Galveston and Houston between 1911 and 1936.It travelled the approximate route of the Gulf Freeway, and was removed because they were "tired of letting the niggers ride for free" (source: memory of my father, used as an example of the racism in Texas society in the past by my father).

Bob Ebersole

Hi,

The truth is even worse then you think. The Galveston and Houston Bluebird Line was one of the fastest interurbans in the US AND was still in the black when Stone and Webster shut it down.

They saw were things were headed and decided to convert to buses instead of replacing the classic wood coaches with new high speed lightweights like Johnston, Gloversville and Fonda, Indiana Railroad and Cincinnatti and Lake Erie did. That said, those three lines invested in new high speed cars and went under within 10 years.

See if you can find Interurban Press's "The Bluebird Line". It is a soft cover that occasionally comes up on Ebay. Also, NWSL sells and O and HO Scale models of the coaches.

Charles

It's interesting to see that both the central planning as in France, or some grassroot commitment as in reviving many abandoned rails in Germany actually work.

Switzerland is the best example that rail can even get the support of the voters. Zurich has often been called the city with the highest quality of living in Europe. And these huge tunnel projects, all approved in a referendum.

In Berlin, some of the busses and trams have their own lanes, so they don't get stuck in the traffic. They can also control traffic lights and signals, so that the cars have to wait...

Parking in the center has become expensive, too. A rail ticket is cheaper. Or look at London with their congestion pricing.

A combination of more attractive rail services and alienating car traffic helps people to switch as well.

In 1998, the Swiss nation voted to spend 31 billion Swiss francs to improve their already fine RR system (perhaps the best in the world). About half goes to those massive tunnels.

There were several goals for such a massive project(s) but #1 was to move freight off trucks and onto (hydro) electric rail.

1 billion CHf of the 31 for quieter rail cars. 240 kph pax service (160 kph for specialty freight on the same tracks) from Zurich to Milan and 200 kph Bern to Milan, etc.

Adjust for population and currency, and it would be like US voters approving $1 trillion.

Best Hopes for Long Range Planning,

Alan

Moving freight off tracks has not worked well in Europe because of all the different technical systems and regulations in all the countries.

We will now get ERTMS (European Rail Traffic Management) and ETCS (European Train Control System), and the trains are more and more compatible with the different power systems (15kV 16,7Hz in Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Norway, Sweden and 25kV 50Hz in France and most other countries).

Deutsche Bahn moved 306,7 million tons of goods in 2007, 266,5 in 2006 and 1,864 billion passengers in 2007, 1,785 billion in 2005. Deutsche Bahn operates 34122 km of tracks, that's second after Switzerland per km².

So, after a long decline, both freight and passengers are increasing again, and finally, the countries cooperate. A couple of years ago, it was unthinkable that a French TGV could move far into Germany, or a German ICE far into France.

Now, there is a TGV Paris - Stuttgart - Munich and an ICE Frankfurt - Paris.

Slowly, slowly we are moving ahead. To expand your point, railfreight is most profitable over distances of say 500-1000 km, a distance which cuts across borders from most European cities, but there is a great number of technical issues that result in incompatibility, even if there would be no bureaucratic obstacles. Thus railfreight has a much lower share than in the US!

Eliminating all of these obstacles is a herculean job. Unfortunately, the second level of ERTMS (which relies on cell phone communications technology) is so far a running technical failure, causing delays for several new high-speed lines, so there we have to wait. On the different supply systems issue, multi-system locomotives solved the problem rather well. Different cross sections (gauges) was already dealt with for freight, now high-speed trains are standardised in that, too. The most spectacular and expensive integration policy is Spain's aim to re-gauge its complete rail system to normal gauge (over decades).

A little clarification: what you talk about is the NEAT aka AlpTransit project of the Swiss federal state, what my diary and Siggi talked about is the project of the canton and city of Zurich. The latter involved a 5-kilometre and a 10-kilometre tunnel, and another 6-kilometre one in preparation, pretty massive undertaking for a mid-size city.

The NEAT project involves the half-finished 57-kilometre Gotthard Base Tunnel, and the 34.6-kilometre Lötschberg Base Tunnel, about whose recent opening I wrote a diary over at European Tribune.

But what you say is valid for both projects: population-adjusted, they mean the possibility of massive popularly supported rail investment.

Kent Jones made the comment that we won't see progress until rental car companies start providing bicycles for hire. Then we know things have turned a corner.

The main German rail operator offers "Call a Bike".

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Call_a_Bike

Paris set for bike-share scheme to cut congestion

I was in Paris last week and these are being deployed all over the place. I wonder what happens when advertising spending dries up due to peak oil induced recession-depression though?

I look forward to Jerome's "first ride" report.

The stations are literally popping up everywhere - I have 3 within 500 meter of my home. I expect to use them to get to the metro station for work, as a station a bit further away is more convenient than the nearest one; my wife expects to use them to go pick up the kids at school. In both cases, it replaces traffic on foot, but it will occupy road space and will hopefully encourage others to do the same. Once you have bikers everywhere on the road, behavior will change.

I expect we'll move around more, taking advantage of the available bikes.

As to the recession, it won't matter as the infrastructure for the bikes is built now and will remain - most of the cost is upfront and is paid for already.

Another point to note is that they take up parking space, which will further make it difficult to drive into Paris. studies have repeatedly shown that parking space availability (or the lack thereof) is the single most important factor in driving traffic up or down in Paris.

In fact, after several decades when new buildings were obliged to build underground garages to alleviate surface parking shortages, city regulations now *forbid* underground garages from being built with housing buildings...

I wish more Americans would take advantage of bicycle commuting and mainly for health reasons. The upper midwest and upstate NY were colonized by northern europeans. The problems with obeisity are rampant here. When I visited Germany, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France in JANUARY I saw (1) much fewer obese people and (2) people bicycling to work. It's the same genetic stock but in one part of the world you have lots of obeisity and in the other part you have much less. The difference is activity levels.

The only place I have seen such winter bicycling in this country is when I lived in Madison, Wisconsin and had to commute by bicycle. There just wasn't any parking and when you found a space YOU DIDN'T DARE LEAVE IT.

In my own life, I notice that during the summer I lose 10 to 15 pounds during the summer if I bicycle and I don't lose weight if I ride my Vespa.

This is my current mantra when I choose between forms of transport.

More bicycle commuting = more weight loss.

More cars commuting = chunky Charles.

So, I hope that the less available car parking in Paris does encourage mass transit and bicycling for the health of all.

Charles

When I see an adult on a bicycle, my faith in humanity is restored.

H.G. Wells

Right on. For bicycle commuting, which I did for years in two previous places I lived at, one can use streets, but it is much better and safer if we build infrastructure for that, too, especially in left curves. Bike paths, bike lanes, storage rooms, and showers at workplaces are a good thing, too.

While the construction of such infrastructure is going on all around Europe, still something more is needed: biker attitude. In many places, car drivers just shit on bikers and endanger them on the roadside or park across the bike path, and often public authorities build only alibi bike paths that are too narrow or full of obstacles. It is a completely different feeling when in Frankfurt, car drivers are extra-cautious to not park with the car intruding half a centimetre into a bike path, for fear of militant bikers just climbing over their cars.

I'm all for bike storage rooms and showers at work, but the image I have of 'bike paths' is the suburban Maryland paths that often run through isolated park space along the big creeks that run into the Potomac. That's the sort of park into which Chandra Levy disappeared. I've ridden alone on these paths, but I wouldn't want my women folk to do the same.

When I bike, I want to be near the action and to be able to stop at places along the way.

Well... the bike paths I had in mind aren't leisure routes but 'commuter' routes that mostly run alongside roads, and bike lanes take room from cars on roads, but frankly I find this fear of parks excessive. On one hand, if bike paths are well-frequented (and if there is a good network and many people use it as in Germany, they are full of bikers), you won't be alone. On the other hand, the chance of being caught by a serial killer in a park is less than the chance of being hit by a car or collide at full speed with another bike 'near the action'.

Many architects and urban designers have proposed and built alternatives to urban streets, separating walkers from drivers with the best of intentions (and probably inspired by La Rambla). They rarely work well. Most of those alternatives are lifeless and unsafe in comparison to a street with both autos and pedestrians, and yes, bikes.

My feeling is that while bucolic bike paths are great for exercise, people on their daily routine usually want to be, and ought to be, on streets - interacting with other people, seeing who is holding hands with whom, what the pretty girls are wearing, etc.

I think removing bikes from the street to protect them from autos marginalizes cycling as a commuting or recreational activity. I see cycling as a better choice than hopping in the car for every errand so I want to see bikes in the street and parked in front of every shop. We have plenty of roads already, so why not transition them from auto traffic (which we expect to decline) to bike traffic rather than building more infrastructure?

I tend to agree.

Narrow one-way streets allow more room for people.

I live on 28' wide streets with parking on both sides. 32' wide is the minimum for new streets.

I would like to see many two way streets converted into one way streets with the other lane turned into 2 bike lanes.

Best Hopes for Better Bicycling.

Alan

By the way, any CriticalMass participants here?

Here is the head of the rally during the April 2007 event in Budapest, which drew 50,000 according to police:

I'd prefer bike lanes where possible, too (and did wrote about them upthread). But bike paths are also useful, be it on the countryside where roads are narrow, or where cars are led around but bikers can take a shortcut.

I note that on my daily ride on the outskirts of Frankfurt/Germany, half my route was on a bike path alongside a country road, another half along side streets, mostly 30km/h (18.5 mph) zone (still I had a teeth-breaking crash when turning a corner & hitting a car parked too close to it); while when I bike-commuted in Budapest, there was no bike path on my route, so I risked being hit by a car on normal roads. I was fortunate to cycle on bike lanes only on excursions.

I recently had an accident, too. A car door was opened at an unfavorable time. Nothing happened to me, but to the bike and the car.

The road code is very clear in this. A car driver must make sure that no-one else is hurt when opening a door.

So, the guy had to buy a new bike for me and get a new door for his car.

That's right that way. But how long did the trial or pre-trial agreement take? A friend of mine who had a similar accident had to keep his bike in a ruined state for one full year (it was considered evidence) until the payment was decided, pretty silly. (Though this was over a decade ago).

The insurance of the car holder has to pay. In my case, the driver payed me in cash, because else the monthly payments for the insurance would have increased.

I had also called the police, so the case was clear.

I note that when the first such system was introduced in Vienna, bike theft was a big problem. I don't know the current state of affairs there, but word is that in another French city that tried it, if I am not mistaken Lyons, the system is considered a success.

We've had these in Helsinki since 2000. Unfortunately people haven't respected them enough, so a lot of them have ended up in a bad way.

As a matter of fact this was tried in my home town in eastern Finland in the late 80's; the project was discontinued because some drunken people broke these bikes and threw them into the river... :(

I think that the trick is to use bicycles that few would want to steal.

At SUNY Cortland, we have a yellow bike program where we take old 60's era 3 speed bicycles and turn them into single speeds. I occasionally help out in the repair department. The students and faculty do use them a lot and I have learned to love women's bicycles with high handlebars: especially the old Raleighs and Columbias. Very easy to ride.

There are several problems though and the first one is a little ironic.

(1) SUNY Cortland is built at the top of a small but steep hill. As a result, most of the bicycles end up at the far end of the campus at the lowest elevation. The oh so fit student (of which many are physical therapy majors) complain that its too much work to ride them up hill. This makes 38 year old me smile and I sometimes will ride 2 bikes up the hill to resupply the top.

(2) Drunken frat boys jump on and wreck wheels. It's never women. It's always some stupid meathead.

(3) We lose about 10 to 15 bikes a year. Usually I see the town under underclass on them so I don't say anything. I mean, do you really want to take away a bicycle from some derelict when it could be his only mean of transportation? I'd rather have a drunk on a bicycle then a drunk behind the wheel.

So yeah, we do have problems with assholes wrecking bikes and the underclass borrowing bikes pernamently. But it is so nice to step outside on a nice fall or spring day, grab a bicycle and ride.

Charles

1) in Lyons, they noted also the tendency of bikes to be taken from high points and dropped at the bottom. They now have teams to carry bikes up to the high elevation points. This is planned in Paris as well.

2) The bikes have been designed to be heavy, sturdy and tough. We'll see how it goes.

3) I imagine they'll have a replacement budget. Note that you have to give a credit card guarantee to rent bikes, so if you damage it, you may be charged for it (if it can be attributed to you).

I can't help thinking that -what is essentially public transport- has a serious image problem in the US. It seems to have permeated the America psychie that if you want to go from A to B you go by your own car and nothing else is good enough.

In Barnes -one of the nicest and wealthiest parts of London- there is no tube system hence you get people who live in 2 million dollar+ homes (i.e. most of them) waiting for the frequent buses to take them to Hammersmith where they catch the tube to their high paid City jobs.

Before you get the remit for large scale spending of tax dollars/yen/pounds/etc. you need to have the mindset that this investment is a good one -and in many countries it just isn't there...

Regards, Nick.

I hate it, but a good sales pitch is to re-package and rename the thing. That we talk today of 'light rail' is in no small part because of the first British and French new tram projects that didn't wanted to be called tram.

In the US, "car culture" is a massive psychological investment.

The car is not really for transportation... it's for privacy and filtering out people you don't like (anyone different, poorer than you), for making yourself feel good (material status, like the shoes or purse or clothes you wear), and for sex (the afternoon fcuk, driving to the next town without your family's supervision, etc).

With this car culture, therefore, all people who take public transit are poor, minorities, dirty bums, old, etc.

The only case where this isn't true that I've seen (and i haven't traveled the US extensively) is the East Bay-to-San Francisco line of BART. In this case, a majority of riders are white or whitening; seeking, suffering or enjoying affluenza; and working higher-paid office space-type of jobs in the human filing cabinets downtown.

I ride BART daily myself on this route which is why I can say this definitively.

Other than this... only in college towns or super dense areas like DC/NY/LA metro do people take the bus or train. Or when there is an Oakland A's baseball game, some people from the 680/880 corridors take BART as a sports stadium shuttle...

This is a wonderful review, thank you. I'm sure I'll be referring back to this post as a technical & planning reference.

Looking to the near future in the U.S., Professor Arthur Nelson forecasts a large increase in demand for transit oriented living. Nelson draws on studies of planned transit lines and residential demand to conclude that nearly half of new growth in metropolitan areas could be transit oriented development, within walking distance of rail stations.

The large majority of Americans (192 million in 2000) live in urbanized areas, at an average density that is suitable for paratransit service. Paratransit includes carpools, vanpools, subscription buses, jitneys, shared-ride taxis and on-demand (route-deviation) services. Paratransit has limited appeal today, but will become more popular as fuel prices increase.

There is an unsatisfied demand for more walkable, transit-served neighborhoods in the U.S. In the long run we should meet that demand with the systems outlined by DoDo. In the nearer term, paratransit is a transportation option that will allow suburban dwellers to weather the short and medium term effects of Peak Oil with minimum disruption.

More at Fun with Density and Transit Statistics.

Transport that requires subsidies are not sustainable infrastructure.

For much greater capacity, PRT (Personal Rapid Transit) can be operated at a profit. As Just-in-Time replaced Mass Production by greater efficiencies, so can personal, on-demand mobility displace Mass Transportation. PRT is rail, it is just ultra-light rail.

Here are some studies that I have collected:

1970's vintage system: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ERdF0FK-2io

Recent EU Study: http://www.jpods.com/JPods/004Studies/060322_EUStudy.pdf

Recent Swedish Study: http://www.jpods.com/JPods/004Studies/InnovPTS2_Swedish.pdf

Recent Canadian Report: http://www.jpods.com/JPods/004Studies/CSTWinnipegGilbert_0604.pdf

Background on Morgantown (1975 version of GRP/PRT at night): http://www.jpods.com/JPods/004Studies/morgantown_TRB_.pdf

Princeton University Study: http://www.princeton.edu/~alaink/Orf467F04/NJ%20PRT%20Final%20Small.pdf

Industry site: http://www.advancedtransit.org/

System being built at Heathrow: http://www.atsltd.co.uk/

System being built in Sweden: http://www.vectus.se/eng_index.html

System we are working on: www.jpods.com

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

For much greater capacity, PRT (Personal Rapid Transit) can be operated at a profit

B S !

See the soon to be bankrupt Las Vegas monorail (operating on a route where the public bus made a profit, the LV Strip) for another "for profit" gadgetbahn claim.

At least LV used technology already in use at Disney parks.

Your capacity claims are based on worthless paper studies that do NOT correspond to realistic operating conditions.

One can go today to Morgantown WVa and Miami & Jacksonville FL and see comparable technology to the Heathrow & Stockholm in service for decades. *SKY* high costs per pax-mile !!

Terrible mistakes to build.

Best Hopes for PROVEN technology, we do not have time to waste on snake-oil,

Alan

More of what is not working will not work.

Cars displaced trains because of better service. Car can only be displaced by something that offers better service than cars.

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

Cars displaced trains because cars were heavily subsidized - free roads, free parking, free pollution.

Take away the free roads (London), the free parking (Paris, Hamburg, Berlin, Munich, Frankfurt), and the free pollution (taxes), and people start to use trains again.

Given the incentives and much greater availability of trains in Europe, 80% of trips are still by car.

Here is an EU Study on PRT is the "personalization of mass transit".

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

More of what is not working will not work

Another false claim by the vaporware salesperson.

When another Urban Rail extension opens, the uniform experience is that ridership density increases on the older parts of the system. Increased density improves the economics.

Single lines rarely have revolutionary effects. Systems are required for that (Such as DC commuters going from 4% bus to 40+% rail + bus, with large scale TOD).

More *IS* better for Urban Rail.

Miami is a case in point. They built what was considered a failure in the 1984/5. A PRT type system crawling around downtown and a single 20 mile heavy or Rapid Rail line with poor ridership and minimal TOD.

But when voters dedicated a sales tax to building a 103 mile system (I was told 90% of existing population within 3 miles of a station and over half within 2 miles), TOD exploded and ridership increased as well.

In 2004, I saw 15 of 23 construction cranes within 3 blocks of a Metro station. Miami is actively reforming itself around the Urban Rail Lines. As more lines open, this effect will increase.

The solution to not enough ridership or TOD on Urban Rail is MORE Urban Rail, not experimental prototypes with unknown costs and operating problems,

Best Hopes for Proven Technology,

Alan

Beyond the points made by others (with which I can only agree 100%): all the projects I listed that boosted ridership beat cars for that ridership. Because they gave better service.

I am willing to believe that your dream system works if a large-scale demonstration is built and works for five years.

Almost all transport is or was subsidised in some form. Today the magic word is externalities.

On a categorical rejection of subsidies, I guess we have fundamental philosophical differences. The goal of public transport is -- transporting the public. If the way to make ticket price affordable to the lower deciles is via taxes, that's a redistributive policy, and I support that. And it's sustainable.

I think subsidizing riders is a good idea. I think subsidizing industries is a bad idea. If we had subsidized few roads we would have possibly not killed the trains.

If commercial companies must add more value that resources consumed to compete (make a profit) they will stay focused on providing value to their customers and cutting their consumption of resources.

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

It's only an anecdote, but I remember how when I lived in Boston and Cambridge, I only rode the public transportation where I did not need a schedule because it was regular. If I had to have a schedule, I knew it wouldn't work except as a special "event". A different mode of planning.

cfm in Gray, ME

If we could build on-demand systems, people could travel at their convenience. Also the capacity is much greater.

Here is a graph showing seat capacity for:

200 seat light-rail, 10 minute headways

50 seat bus, 5 minute headways

cars and PRT with 3 second headways (cars in rush hours often trim that in half).

A good thing about cars and PRT, if no one is moving, there is not need to move a vehicle just to keep a schedule.

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

if no one is moving, there is not need to move a vehicle just to keep a schedule

So, as people go from their homes in the morning on PRT, the PRT will park at their workplace or school until they are ready to go home ?

This is part of the strategy for Paris's new rent-a-bike plan, but even there vans will collect a small % of bikes from one location and shuttle them to meet peak demand.

Else, you are going to have to move PRTs around empty to meet other demands.

Even at airports, there is not a balanced flow at all times.

Another false claim by vaporware gadgetbahn,

Alan

Hi Alan

Sorry to confuse you. There is no need to move a vehicle to keep a schedule, as with trains. There will be dead heading vehicles moving to meet demand.

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

Hi Bill:

I agree that cars often run at very short headways,this is why "following too close" is the leading cause of collisions folowed up by "speeding", which is in many cases another way of saying the same thing.

10's of thousands of folks are killed, and over a million injured every year in North America alone every year because of this.

So I'd suggest that advocating for the implimentation of another system which is "unsafe by design" is to say the least unethical

So, could you post links to what data you are aware of on the jpod system which might address these concerns?

Thanks.

Hi John

I do not think cars are safe. I ride a motorcycle a lot in the summer; I know very few drivers are alert.

Automated systems generally have exceptional safety records as to roller coasters.

Morgantown has logged 110 million injury free passenger miles (since 1975). TRB Report on Morgantown

ATRA Site

JPods' mechanics are essentially off-the-shelf roller coaster wheels confined within a box beam. Here is a link and quote from a CBS interview with the Amusement Park Industry Association:

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2002/06/25/earlyshow/living/parenting/mai...

Q: What kind of amusement park injury numbers are we talking about here?

Powers: 320 million people visit amusement parks every year and the Consumer Product Safety Commission reports 6,500 injuries and one ride-related fatality. And the year before, we had zero fatalities.

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

Seems from the PDF link you posted that the minimum headway on Morgantown is 15 seconds, enforced by a "moving block" system, and that in practice the minimum headway is 1 minute "at speed" when out of the station. So I don't see it being relevent to the jpod system design with its short headways.

Also, having looked at the jpod website, I don't see any "fail safe" braking system in the drive unit i.e. it looks like the car requires power to the drive unit and the drive unit to be functional to come to a controlled stop, though certainly I might be wrong here...

Morgantown has redundant penumatically actuated disk brake systems which operate in a "fail braked" mode as far as I can tell.

I can't find any roller coaster design that needs the system to make automated decisions about congestion or obstructions on the track ahead followed by an automated braking command in order to avoid collision, so I don't get the relevence of that reference either...

You are correct in that JPods face more variations that roller coasters.

On our current very small demo, we use just the motor to break. As we move into production later this year we will have an emergency fiction brake system.

There are specific standards. In addition we want our systems to be so safe that safety as an obstacle to deployment is never questioned.

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

But getting the car moving is a trivial problem compared to the control/speed/braking/headway problem....

So to start touting the idea without detailed proposed viable solutions to the "deeply hard" problems, the solution of which are critical to the practicality of the idea, first, is really I'd suggest just to invite ridicule or at least be "written off" by anyone who has considered the matter in any detail

The Wright Brothers invented flight, not the 747. I believe what is important is an iterative process; small steps, iterate often. There is rarely AN ANSWER. By implementing a process of adhere to what you know, test assumptions, plan to change, execute, adhere,... you can home in on what works.

Our first JPods networks will not employ the patent for distributed collaborative computer networks moving physical packets, a Physical Internet. They will be simple point to point mechanical roller coasters (slow and uninteresting with long headways). In difficult times doing what is simple, and iterating, is achievable.

bill.james@jpods.com

It costs less to move less

I thought Daedalus invented flight. :-)

When is no one moving?...

Your comparison is completely out of the ass. Why not take a 400-place tram at 3-minute intervals? Or what about a 1000-seat rapid transit train at 5-minute intervals? Or a 500-place subway at 1.5-minute intervals? There are real existing rail lines in the world way beyond 5000/hour.

10 minutes headway for rail?

The Chicago transit authority had a 2 minute headway on its elevated during rush hour in the 50's WITHOUT computerized scheduling.

200 seats * 25 trains = 5000 people.

And this was when the North Shore Line and Roarin Elgin were also running trains on the same elevated to Milwaukee and the Fox River Valley cities (Aurora, Elgin, and Batvia) respectively on the same tracks.

Charles

P.S. I have included a link to a neat NSL poster but I don't know how to get it to show.

![]() http://www.northshoreline.com/Nsl74ad.jpg

http://www.northshoreline.com/Nsl74ad.jpg![]()

Denver Colorado is a good example of a successful rollout of a new "light-rail" system. The city has a population of 500,000, and the metro area 2 million, but the area is rather sprawling, i.e. Denver has a lower density than a typical Eastern US or European city, something that makes mass-transit less efficient. Plus, of necessity pretty much everybody has a car.

The political difficulties include the fact that people are fairly conservative when it comes to government projects (damn socialists) and taxation, however the good voters funded some initial tracks which were so popular that a huge expansion has been designed with further funding support from the voters for an accelerated, 12 year construction project of . Presently total track is 35 miles (50 km), with ridership over 60,000 on workdays. By 2025 the "fast-tracks" investment will result in total track of 150 miles.

Perhaps the most significant economic result has come from the intense redevelopment at the stations. These are typically much denser developments with apartments, "town-centers", shopping and parking. Here are some positive newspaper comments:

And in the end, the parts of the metro area which most opposed spending money on a government light-rail project have flipped to demanding the earliest construction for new lines in their areas.

More detail.

The Southern half of Denver will get Light Rail, the northern half commuter rail (they were looking at electrified commuter rail to the airport, but costs ...) The rest of the commuter rail will be diesel.

Due to rising construction costs, economies are being considered. Single track in some sections, less Park & Ride, etc. And federal funding is being tied up and slowed.

Still, Denver will be *FAR* more ready for post-Peak Oil than most US cities.

Best Hopes for more federal funding for Denver,

Alan

Well, at least there will be a good possibility of completing the system in the future, e.g. commuter rail network to the South and the light rail one towards the North. Good luck for Denver.

That's five times the motor vehicle travel savings previously predicted in a separate DRCOG review of the FasTracks plan earlier this year

The same agency, within a year, came up with two estimates on VMT reduced by FasTracks that vary by 500%.

I assume the second study looked at TOD effects and the first one did not.

I have long stated that the indirect energy savings from TOD effects of Urban Rail are larger than the direct savings. 4 indirect to 1 direct seems to be the Denver estimate.

Do you have a link to these studies ? I could use them.

I just claimed that indirect > direct, but never specific multiples (4:1 sounds good to me :-)

Best Hopes,

Alan

You'll have to look at DRCOG, Denver Regional Coucil of Governments.

I don't have any specific answers. I think the general answer is that different economists, changing economy, different assumptions and different measuring sticks probably have something to do with it.

Perhaps they estimate low, but especially in the Western US people love the independence of their cars, and many do not have a history of using mass transit. The cities are so spread out that it is hard to do shopping, work, recreation without a car.

In any case, the ridership has been higher than expected. So much so that they have had to order new cars to meet demand, but there is a two or three year lag time from order to delivery.

In the future, the delivery time problem could be gotten around (that is if there is no simultaneous capacity problem on several lines across the country) if there are train leasing companies. With the creeping rail privatisation in several European countries, such leasing companies have been established (which I view as the only genuinely positive effect of this drive).

And in the end, the parts of the metro area which most opposed spending money on a government light-rail project have flipped to demanding the earliest construction for new lines in their areas.

Forgot to ask: could you provide links on this? It would be useful evidence for me to point to in the future.

Rail as a means of Peak Oil mitigation (or more accurately, post PO transition strategy) has plenty of supporters here (including me), but there are limits too and it may be worthwhile to listen to the detractors.

One thing I noticed in this feature piece is the lack of discussion of private railways. Should everything be a government project? Is not rail service worthy of a price, to be paid by a customer?

Remember a few months back when it was BART (I believe) offering free rides after the freeway closure (due to tanker fire)? There were people here and elsewhere championing the "free" nature and claiming it should always be that way. To me that was 180 degrees opposite of what is needed. My experience of rail in the US is this - the operators need to charge me more. Then, they will be able to offer me what I need (more frequent trains and more rail stops.)

The #1 problem with rail (and mass transit as a whole) in America is this: it is run as a charity and not as a viable transportation system. (Perhaps there are one or two exceptions to this, but I'm pretty sure my statement would cover 98% of American cities.) Thus it is despised by those who don't want to contribute to this charity but otherwise may be forced to (via the tax laws.) The charity nature (in the US) of most rail also explains why the implementation (e.g., facilities at the stations) are so lame.

While living in Japan I grew accustomed to well run and useful private railways. I was willing to pay the cost to buy tickets because it offered me a service worthy of my money.

This is not an easy problem to solve, but I am still willing to support publicly funded rail if for no other reasons than (1) to protect and service the ROW, and (2) to encourage US based rail-servicing industries.

The other challenge for rail and public transportation was illustrated by SS several months ago in his featured article here on TOD. The numbers so far show that there has been only small effects upon automobile use. In order to mitigate a significant number of the needs to drive an automobile, rail systems (and integrated transportation systems) will have to expand tremendously. There exists one and only one city (New York) in this country in which I could live my whole life and not absolutely need an automobile (and I have lived in the DC area before.)

So.... rail faces the classic chicken and egg problem. To get to the goal - a rail system extensive enough and well run enough to make a significant impact on the use of the automobile, is the real challenge facing us who live in America.

Let me end by making a pitch for the city... so many times here (at TOD) we see the survivalists talking of heading to the hills... but they forget that the idea of the city is about 10,000 years old and significantly predates the age of oil. And, the city will still be around long after the age of oil. This is so for very, very good reasons.

The question is, what kind of city do we want?

I consciously avoided public vs. private in the diary. It is a contentious subject, and rail construction could be advocated without declaring a preference there. What I think is important is the integration of rail systems, i.e., even if lines in the same area are owned/run by several different carriers, passengers don't have to face a pricing and timetable chaos if they need to travel on more to their destinations.

But here I give my personal opinion. I don't think high of rail provatisation.

There is the objective of public transport. What you say about paying more for good service is the viewpoint of the well-off, and while most people are well-off in Japan or Switzerland and there is no such underclass as in the USA or even Britain, elsewhere, they should be considered too. Meanwhile, a large part of the middle class will choose the car on price even if train service is better.

On Japan, I also note that the high population and building density make it much easier for rail to compete, even at higher prices: people will choose it if the alternative is 24-hour traffic jam.

Both in the case of Japan and Switzerland, I note that privately-run railways own their own tracks, and rarely compete with each other -- instead, they even cooperate. What I really don't like is the EU's current policy of separation of infrastructure and operations and open-access competition. Of the several problems I see with it, the chief one is the reduction of the profit of busy mainlines in price competition, so that that money can't be used to maintain feeder branchlines.

In the case of Switzerland, I also note that the current trend is just the opposite of what goes on elsewhere: for a few years now there is an on-going consolidation among the private railways, while one major private that went bankrupt was merged into the (profitable) state railway, and the latter's boss advocated keeping railways integrated despite benefitting from German and Italian open access.

Dodo - thanks for the reply.

As it seemed to me you had indeed avoided the issue (of private vs. public) I felt it was necessary to raise it.

Because it gets to the difficult but necessary problem - implementation. If you are wanting to go on a public funds spending spree be assured the issue will be raised.

As an implementation specific example, note that several of the subway systems in Japanese cities have (some, but not all) city subway lines connected seamlessly to private rail systems. The concept of private operators on public lines does work well; it is a win-win scenario for the city and the private companies. In the US such implementation may or may not be viable for all locations, but it may well make great sense to have the medium to small cities contract out to local private rail lines to integrate into larger rail networks.

From experience, it is indeed delightful to be able to travel from within the city to some other community, without having to change lines (or even seats!) The integrated ticketing schemes found in Japanese cities is a wonderful convenience that is the icing on the cake.

As TOD is a Peak Oil website, I think it is important to keep in mind the underlying basis for the need of alternate transportation means. According to the majority of PO thinkers, by 2050 gasoline will no longer be used daily by most people for automobiles (as petroleum will be too valuable and needed for commercial, military, industrial uses.) Gasoline will be considered a true luxury and a great deal of the population (in the US) will require non-automobile transportation for daily life.

Thus the requirement for implementing rail systems is a given (if one accepts Peak Oil as a concept, as well as understands the limits of biofuels.) One doesn't have to approach local rail systems as a charity project (in my words.) You don't have to reference marxist concepts such as "class". People and things will need to get from point A to B, period.

Thus I (and I suspect most TOD readers) would challenge your statement:

Your statement is true for 2007. Again, however, PO is expected to change the buying habits of the average American (and everybody else too) over the the next couple of decades. Will your statement be true in 2037?

Automobile transportation in the U.S. is deeply subsidized. Considering all federal, state and local expenditures on highways, direct user fees (gas taxes and tolls) cover 39 percent. Sixty-one percent are covered by vehicle taxes (regardless of whether the vehicle uses the roads or not), property taxes, income taxes, and bonds. Municipal streets are generally funded by bonds and property taxes, and in some cases sales taxes and state income taxes.

That means people who drive less are subsidizing those who drive a lot; those who drive mainly on city streets are subsidizing those who mostly use highways.

See: Fueling Transportation Finance: A Primer on the Gas Tax

http://www.brookings.edu/es/urban/publications/gastax.htm

A related report along these lines:

Improving Efficiency and Equity in Transportation Finance

http://www.brook.edu/es/urban/publications/wachstransportation.htm

Transportation finance is increasingly dominated by a politics of expediency, and as gas tax yields sag, reliance on local transportation taxes surges. America's system of transportation finance is quietly but steadily being restructured from fuel taxes to property, income and general taxes.

Whereas in Europe the exact opposite is true.

For many years now a combination of Vehicle Excise Duty (annual charge known as Road Tax as it used to pay for the roads...) and fuel duty in the UK is far higher than the, construction, maintainance & health costs associated with car use. And thats before the Value Added Tax (sales tax) receipts on car servicing, parts & cleaning and corporation tax on major car manufacturers is added into the equation.

If petrol, diesel, and car use were banned tomorrow in the UK then the treasury would sink under the weight of its debts.

So while it might be true in the States, in Europe the automobile is a net contributor.

And I really wish folk would stop banging on about the roads being free. They most definantly aren't. The users pay their annual charge which more than covers maintainance and construction of new roads. The reason the roads are so cheap is because of very high utilisation, which helps spread the cost among many users. Sadly the railways don't have such high utilisation (in many instances) and in the UK are currently facing a 40 year backlog of upgrades & maintainance.

Andy

In Germany the vehicle taxes go to the state (not the federal level) and covers the costs of municipal roads and maintenance.

The more expensive federal roads are financed by fuel taxes and recently by tolls from trucks. The fuel taxes are significantly higher than the expenditures for roads, the surplus goes into the pension systems and thus makes labor cheaper. There is a hot debate, though, if the car and fuel taxes really cover all the external costs of cars, such as emissions, pollution, accidents, deaths.

The railroads are financed by the federal budget, too. Most of them are in good shape again, after a 40 year backlog.

The government spends still more on federal roads than on rails.

So far in the US there only are two types of centralized city you can get.

The ones where the city centers are cleaned up and made attractive and the ones which are not. The former are trendy but extraordinarily expensive (ie starting at a million U$S for a small flat), the latter are so unsafe and full of squalor as not to be acceptable.

Planning, tendering, boring, fitting out with concrete lining and tracks and electronics of this 40.5 km all-tunnel line; station construction; and purchase, testing and commissioning of subway trains was all done within four years and on a budget of only €1.1 billion!

The bloated cost of subway and rail construction in the USA is a high hurdle for transit advocates.

Would it be possible to dig deeper and compare subway construction costs in Madrid/Paris and Los Angeles, my home town? I would love to see projects such as the Expo Line to Santa Monica and the "subway to the sea" proceed ASAP.

Could the "bloating" be due to union benefits, safety restrictions, construction codes, lack of competition? I don't know and would love to find out.

I have spent quite some time on this issue, because it is critical to both speed of construction as well as volume.

I have talked with the foreman in charge of drilling a new water tunnel in NYC (MUCH cheaper than subways) and the contractor who over-built the 5 mile Canal Streetcar Line for $150 million (we built our own streetcars in-house for $1.5 million each, units #6 to #24 about $1.1 million each).

It is the PROCESS required by the FTA to slow down the construction of Urban Rail. The national engineering firms often get 30% of the total costs (should be 8% to 10%) and gold plate as much as they can get away with.

Studies, studies, studies, public outreach, vastly over-engineered details, Art in Transit is an extra 1% wasted, and delay, delay, delay.